Zdeněk Kovařík

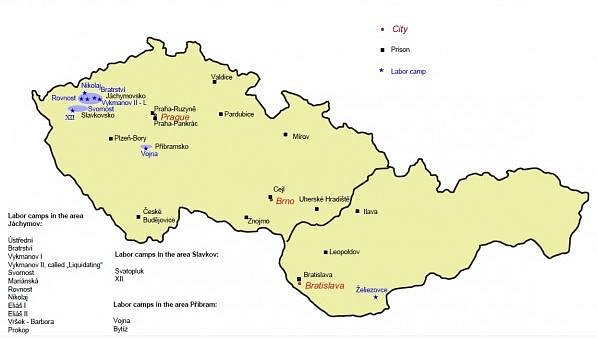

Zdeněk Kovařík was accused of high treason in a show trial called „Group JU1" and sentenced to nine years of prison. He had to work in the uranium labor camps in Jáchymov until 1955 - he spent two and half years in the labor camp „L" called also „Liquidation camp" and two years in the forced labor camp Nikolaj.

Interview with Mr. Zdeněk Kovařík

"Find your goal in life and go and get it until the very last breath." ~ Mr. Zdeněk Kovařík

Interviewer: Tomáš Bouška

This interview's English translation has been gratefully edited by Ms.Olivia Webb.

At the beginning of our interview I would like to ask you about your childhood.

I was born in 1931 in Hradec Králové,[1] where I lived for practically the majority of my life. There were four of us kids, and I was the oldest while my youngest brother was eight years younger. As for my youth, I can say that I had really wonderful parents and a great childhood. Like I said, I had three siblings and we all had some duties since my parents didn't really have it that easy. My father was a laborer who worked as a city bus driver in Hradec Králové. He had to work hard to feed four children. Fortunately, I had a good advantage because I was quite independent but still didn't act out against my parents. I was also - well I don't want to praise myself, but I was quite hard working, which allowed for plenty of time for my hobbies and fun.

Can you remember the 1938 mobilization or the beginning of the war?

After the German invasion I could already remember such moments as when my father got home from two mobilizations - one in June, and another in September 1938[2]. He came and he was angry and sorry at the same time, not knowing whether he should cry or take a shotgun and return to the borders to start shooting someone there. That was something like our first introduction to what it's like to find out that you are helpless. I started to understand that a person should never give up easily, and that one always has something to fight for. At that time, already in 1939, I wanted to join Scouts[3]. Unfortunately after the Germans came Scouting was prohibited, so it only remained a wish inspired by my friendships with those who used to go to Scouts. We were really lucky that we were such a nice group of boys. During the War the Gestapo locked up one whole family in a house in Hradec. Since they were doing that at night, we only found out what they did with the people later on. Then it was something as an inner resistance of things happening around us. There lived next to us Karel Kodeš, who was a couple years older than me He was probably eighteen at that time. Later he immigrated, and after the War was over I found out he had become a member of a flying squadron but had been shot down over the Bay of Biscay. These are the kind of memories that have always motivated me through hard times and when I think of them they would motivate me to do something.

What was life like after the War?

Right after the important days of May 1945, I quickly joined the Scouts. I joined a good group again, which was lead by a couple of young Scouts. The whole group was called "War Twins." Later on, these guys got state honors for their Anti-German and Anti-German occupation activities. One of them was even shot during their partisan activity. His name was Karel Šimek and he died tragically in 1945 when he was shot by Germans. He was cutting the telephone connection from Hradec to the airport. So these older scouts who had such incredible experiences during the War were teaching us how to do these things. It was kind of enlightening to learn that you can always do something to affect what is happening. The Scouting activities finally led me to prison, but these are already different things to talk about.

Were you lucky to finish school after WWII?

Right after the war I started an apprenticeship and trained to become a telephone mechanic. Right in 1950 I began going to school and started at the College of Industry in Pardubice[4]. One month after that I was locked up, so I was locked up as a student: a student with a high school education.

What did you think about 1948? How did you accept the change of a regime?

It was tragic because I leaned toward the National Socialists. At school we had a really great teacher who was introducing us to quite a few different political ideas. I didn't like some things that the Communists were doing at all, and I had a really big aversion towards them. I remember how we were searching for a camp in 1946 when the elections[5] were just being held. I remember how the Communists prepared the figures and hung them on the square in Bystřice nad Perštejnem - and how they marked them with the voting numbers of the National Socialists and the Populist Party. They made eight or ten gallows, and there they hung these figures, which meant that they were basically burning effigies of these political candidates. So a normal person could not agree with this stuff. It goes without saying that when we were establishing a Confederation of Political Prisoners[6] in the 1990's we were recieving similar letters. I mean threats.

What was your incarceration like and what were you actually arrested for?

The thing I was arrested for I found out much later. As a part of the scout troop we wrote threatening letters and once even destroyed the Advertising Office of the Communist party in Hradec Králové. We hid a small bomb there and then detonated it. It broke the door, the shopping window, and all the posters hanging there. No one was injured, nothing was burned, but it was the night before May 1, 1950. It was a demonstration against what was happening here.

So what exactly did your arrest look like?

I came home from school and the same day I was supposed to say goodbye to a close friend who was about to join the army. We did sports together, and from 1948 participated in regional, county, and national tournaments three times in what was called Zborov's Race. From the regional we moved on to the national championship. Zborov's Race had various army disciplines, including sprinting, swimming, and others. One of our friends was entering the army to join the paratroopers.

On September 29, 1950 I came home from school in Pardubice. About 7 PM, a guy came up to me and said, "I need to talk to you. We are interested in some things." I lived in Slezské, a suburb in the outskirts of Pardubice, and there was a small park about a hundred meters from our house. He told me we would meet over there even though I had absolutely no knowledge about what was going on. He told me, "I am from school I will need some parts for radios and those sorts of things." I just replied that I don't do things like that. I still didn't have a clue about what was going on, so when he saw that he wouldn't get anything out of me he gave a sign and all of a sudden there were some fifteen men before saying, "We are arresting you. We are arresting you," and that was it. Then they came home with me and searched my house. My parents were frightened, as were my three siblings. By 11 p.m. they had transported me to the prison in Hradec Králové, not saying a word to my parents, just mentioning that they would ask me a few questions and that I would return the next day. I came back in five years.

What exactly did they look for during the house search?

They were searching for anything. I was just working on a radio. I wanted to make a radio connected to an LP player because such stuff was not available on the market, but they thought it was the construction of a radio transmitter. I sympathized with Americans, and from 1946, received a bulletin from the American Embassy. It wasn't anything politically against Communism - just a bulletin distributed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But this was also evidence and so we were sentenced for the Americanism. They searched for anything that they could sentence us for. At 11 o'clock they transported me to the prison and there I waited for three days without knowing what was going. They wrote some papers with me and then let me be for three days.

Then they blindfolded my eyes and took me the Ulrichovo Square, where there were the offices of the secret police. That was my first hearing and it lasted from 10 AM until 1PM. They were still trying to convince me to tell them something, but I kept saying, "I don't know anything. I don't know about anything." I wasn't admitting anything so they ended it at night before taking me back to the jail. On the second and third days it looked the same and on the third day they just told me, "Hey, don't be ridiculous - here are the reports. We locked up the others and they've already told us everything that you were doing."

Did you know the people that were written up in the reports that they showed you?

I knew them because we did one silly thing since we agreed on establishing an official Scouts Troop. Unfortunately, another guy who wanted to escape across the border in 1949 joined our group as well. They caught him and punished him with a half year of imprisonment for attempting to cross the border. He was showing off that he had friends he could write to who could come and get him out of prison. He was already somewhere by Jáchymov - somewhere at Vykmanov on C. He probably told this to someone who was already cooperating with the secret police. This person had to have given our names and so they came and arrested us all. That was already after the bombing of the Communist's building. That was the biggest thing we did and the policemen called it "Noisemaker." They were wondering who did that for about a year and half before this "good boy" told them.

What happened when they brought your colleagues' reports and showed you?

I just read the reports to find out that there was also my accomplice named Ctirad Andrýs and another compliant Lubka Škaloud. I thought to myself, ‘Oh, good. There are three of us.' They practically threw out the things that were no longer deniable. So I just told them I agreed, signed it and that was the end. But then they weren't okay with it and they called me back in two weeks. These interrogations took place in a prison in Hradec. My cell there was only a short distance from the interrogation room. It was about ten meters away so I could hear all the interrogations taking place. At night there was either some sort of crying or beating. It wasn't anything nice at night when, all of a sudden, you hear some horrible screaming. First there would be some investigators yelling and then there was the prisoner crying because they were beating him.

There they brought me, and told me that I hadn't told them everything. I denied that and said I did. So they turned me to the wall and I had to squat and hold my arms out straight. On my arms they put a ruler and I looked in front of me and on the wall I saw dried blood. So I thought to myself, "Well this is where all the fun ends. This is where it gets tough." This I repeated to myself about three times. Sometimes they hit me over my arms with that ruler with the strengthened side, but they didn't get anything else out of me. So they let me be and all of sudden in January after the new year they called me up for more investigations again. There I heard again, "You didn't tell us everything." Everything was again the same. Later we found out that Zbyněk Škaloud started to make things up and let his fantasy get out of hand and started to give them names. I don't know whether he wanted to please them or what. That meant that he helped get others arrested, including Květa Pilmanová, who was a friend of ours, Radek Brožový, Karel Havránek, Jirka Pašta or Bohouš Marek.

Do you know whether he did it on purpose or by mistake?

I really think he did it on purpose. Later I found out that he was a real covert. He liked to show off and, because he talked too much, he practically got eight other people arrested.

How did you make it through your trial? Did you have a clue that you could get such a high sentence?

On March 14th-15th, 1951 we stood in front of the court. It was a monsterous trial. It was a public proceeding where they invited all the young students from the schools and the factories. It was held in a court hall in Hradec, and we were judged as a dangerous and frightening danger to society. They were judging us for being Scouts, because even though Scouting was prohibited, we had kept on doing it. The outcome was decided right at the beginning since they were accusing us of high treason, espionage, and I don't know what else; about six of the charges were really serious. They called us Group JU1, and I don't know why it was JU, but maybe from Junák Group and the first one. There were nine of us. Lubka Škaloud got the highest sentence -14 years. Then there was Zbyněk Škaloud who got 12 years. I got the third highest sentence at 11 years. Then behind in a row was Ctirad Andrýs and all these people who are dead now: Ctirad Andrýs, 10 years; Radek Brož, 9 years; Bohouš Marek, 7 years; Pašta, 7 years; Havránek, 4 years; and Květa Pilmanová, who had her eighteenth birthday on the day of trial, got 1 year.

Were your parents present?

My parents were there. There was my mother, my father, and even the girlfriend who I was dating at the time. This young lady waited until my release and we have lived together up until today.

What happened after your trial?

After the trial things happened very quickly because we stayed in Hradec for a couple of days before being transferred to Pankrác. After something like a trip to and from there we went to Jáchymov, where I arrived sometime around March 25. That means that in about ten days after my trial I was already at the labor Camp Bratrstvi (Brotherhood), which was the head camp. We stayed there the night and then they took us away again. Three of our group went to camp L,[7] where the uranium ore[8] was being processed. There we got prisoners' clothes; the majority of people working over there were young. It wasn't very easy work - it was really hard, and not very good for your health.

What kind of job was it and what was your daily routine like?

It was at a so-called uranium ore processing plant called OTK. This workplace was located in Horní Žďár in a village called Vykmanov. Right next to that there was one old camp called C,, and we were at the new camp, which was L. It was also called "the liquidation labor camp," which was quite an accurate name. When I came in March of 1951 there was only one building standing there... well actually two buildings, one was for accommodation and the other was for everybody. There was a kitchen, canteen, infirmary, doctor's office, and other equipment that was necessary at every Camp Like this. What was interesting was that there were no showers. If we didn't ask for showering at the workplace, which was right next to it, then we practically didn't have a place to shower. In spite of these bad conditions we were still able to maintain our hygiene and keep ourselves clean so that we could live through all this.

A little later, in the fall of 1951, another building was erected since the whole labor camp had gotten bigger. They started taking all the uranium ore from all the other mines across Czechoslovakia at that time. We had to construct this other building during the afternoons - meaning after our morning shifts - as an unpaid job. Of course we didn't get anything for it - rather, it was an infringement on our free time. The number of occupants had increased from 150 to 300. The materials were taken to Russia to the place called Čierné při Čope. There was a train called "Věrtuška" which was entirely filled up. When we came there in 1951 there were only two trains leaving per month. After the production increased there were trains leaving every week. By the time that I left in 1953 there would be one train every two or three days. One fully loaded train contained somewhere between 25-30 wagons, each weighting 25 to 30 tons each. There was a lot of material. This was highly refined ore. I talk about this because there were two kinds of material. One was strongly radioactive which was being processed on grinders in the place we called the "Tower of Death." Then there was the second one, which was of a lower quality, and this was freely transported, loaded, and enclosed in wagons which were originally intended for cattle transport. It all was a heavily-guarded commodity, and would always have an escort. In the front and back part of the train there was an armored escort, and there would be about eight people in each who would guard the train through the whole country.

What exactly did you do?

Actually I went though all of the positions, not counting those where they were working on chemical samples. I would also unload material from the trucks, because at that time, the trucks didn't have hydraulic lifts which meant that everything had to be loaded and unloaded manually. The minimum we had to unload was four trucks, but I also had to load up twelve trailers, and these held one ton of material each. This wasn't any fun and I would always thank God that I was so young to be able to survive all this. This was the outside workplace. Then there was a second workplace where we worked on the high-quality ore which was transported in small boxes. These boxes weighed between forty and ninety kilograms (88 - 198 pounds), 45cm, and each had a lid. At the beginning they were sealing them, but they later didn't have time for that so after a while they just had latches so the box wouldn't open. These boxes were measured according to how much radioactivity ach had before being loaded into larger containers. One container was from one shaft. We were taking these small boxes from one shaft for four days until we filled one container. In that box there were from 45-60 tons of material.

When the box was filled until it met the required tonnage, the material was put onto a long conveyor belt. This belt was about fifty meters long and about eighty centimeters wide. The container was narrow, and we had to load everything manually. We didn't get any gloves, so all of our knuckles were scraped. On this belt, the material ran into the first grinder. There was a net above the grinder, the smaller material sifted through while the bigger pieces continued on into the grinder. There, they were crushed into smaller pieces which then ran along the second conveyor belt that was once again forty to fifty meters long. It ran into a tower where everything was sorted and sifted through another net, but this net was finer so it only let even smaller pieces through while the larger pieces [about five centimeters in size] went through the grinder until they were crushed into pieces of about five millimeters. From here everything was taken out, put into a bunker, and from the bunker onto the trailer which was taken to the last floor of the tower. This tower[9] was about twenty-seven meters high and it's still standing there today. That was where that the material was taken out on separating machines and sifted for the last time. When there was a bigger piece left it would again go back into the grinder. So this was how everything would run until the granulated material was no bigger than five millimeters. This final product was then taken back into the bottom floor of the bunker, where the barrels would then be filled. The barrels were about fifty centimeters high and wide. Their openings were fifteen centimeters wide, and into these we had to squeeze sixty kilograms of granulated material from each shaft. It's important to say that some materials from some of the shafts - from Slavkov, for instance - were lighter. So to squeeze in sixty kilos was quite a challenge. Material from Příbram was heavy, so loading that was an easier job. There would be six people who would stand while a seventh was loading the barrel; meanwhile, the other six used tamping irons to pack everything in tighter. Then the barrel was weighed before being moved to the place where it would be sealed. On every barrel's seal you could find a stamp with the information on its original shaft, total weight, and some other specialized markings. Then everything was placed into storage. This storage was very long - 150 - 200 meters on each side. A stamping machine stood in the middle and then the barrels would be taken...well, actually, kicked...from one side of the storage facility to the other. There were about 300 barrels to stack ontop of each other. Finally, the wagon came, we would open the door, and roll the barrels into the wagon. As I already mentioned, this train was called "Věrtuška." So that was the process of the tower.

Were there any other ways the uranium ore was processed?

When I was speaking about the square there was something we called the "Poor Prinder" or "Grinder Three." Big pieces of material would be crushed there again and processed, but this process was slow. It was ground, separated, and then put into the bunkers. From there it was manually shoveled into wagons. The highest quality uranium ore that the camp processed went through Grinder No.2. That was almost clean uranium. That was one of the worst working places since everything had to be processed manually, and from the onset there would be about forty boxes in need of unloading. These were all unloaded onto a big pile, and from there the material would be manually thrown onto the net. Everything that was left on the net had to be picked up and manually thrown into the grinder. The soft granulate was already moving on the conveyer belt, and everything would again be ground down to pieces less than five millimeters. We had to do this process about seven times before it was over. Everything had to be mixed well together so there would be a steady composition of the quality of the uranium ore. So the whole process was done seven times - and this grinding produced a lot of dust. On one side there was a grinder, and right next to that - five meters away - we were working and assembling the materials together. There was no ventilation and we didn't have any respirators or masks. We didn't have anything like that, so we left each day grey or red depending on the uranium ore that was being processed. When we were processing Příbram, the tower would produce dust, of course, and this dust was red since all the material from Příbram was mainly red in color. When we were processing Slavkov, the color was gray-green - and that was a weird color. Finally, when the ore was from Jáchymov the color was gray-blue or dark gray. When we were processing material from Lužnice, we would also know exactly which two concrete shafts were working. After this first half-year we perfectly mastered everything about it.

Do you remember any names of the guards or people who were checking on you there?

There were mainly nicknames since we didn't know their real names, but the commander on L was Píbil, who was later a major in Pardubice. I, for example, found out when I was already on L that I knew one guard. I was asking myself, ‘Where the heck do I know this guy from?' It turned out to be Josef Kulek, one of the Scouts! He used to be a member of the group "War Twins" and he joined the secret police. He started talking to us and suggested that we could be friends and that if we needed something he could work on it for us. I just told him, "Josef, just let it be, and don't even talk about that. Here is the fence...and you are on one side and I'm on the other. The fence is barbed-wire, so you always have to keep your eyes on this." Anyways, he probably got back at me a little because right in 1951 I got incarcerated...and I don't know why, but during Christmas they took 47 people from L and isolated us in the prison. I was one of the twelve who were put into confinement in L and the remaining prisoners were taken to the nearest camp, camp C, for punishment. I was there from December 20 to January 12. Why and for what I haven't found out even up to today.

Could you describe your imprisonment in more detail?

The cell was a small wooden shed and it had two rooms which looked like rabbit hutches. They were about 1.3 meters wide by 2.5 meters long and 1.75 meters high. I was 1.77 meters so I always had to bend when I stood up. They put six of us there and gave us two blankets for the night. We put one blanket underneath and we slept head to legs, head to legs. This is how the six of us stayed until January 12. In the morning we would each get one pot of decaffeinated coffee and one slice of bread. It was a very small slice of bread. At noon we would get soup, but the soup was really watered down; again with a small piece of bread and the same thing for supper. We couldn't wash, and instead of a toilet, we had a small pail. We did everything in that. This pail would be hung on the door for the night - otherwise we wouldn't have been able to lie down. The worst thing was when the guard would rush in at night and open the door until all the contents of the pail would splash out. That was miserable. It's hard to describe it. I don't believe that many people would believe the stuff I'm saying and instead say to themselves, "This man is making it up." But this would really happen.

Have you ever met Josef Kulek after your release?

Yes, I met him when I was a civilian. About a year after I came back, he wanted to talk to me, but I told him, "We have nothing to talk about together." I met him in 1978 or 1979...I don't know exactly. I was working for the sugar refinery in České Meziříčí. I worked there as a designer and builder. We were implementing new technologies when all of a sudden someone was standing above me, and I told myself ‘I know this man.' And it was Mr. Kulek. A year later the secret police called me and asked what I did; how I did I do it; was I behaving myself, and so on. So he didn't leave me alone until the last moment of his life.

How long did you stay at camp "L" and when were you transferred?

I stayed on L for two and a half years - and for the last two years I was in camp Nikolaj in the Eduard mine. This was a special rarity among camps, because from camp Nikolaj on mine Eduard you would walk through a special corridor for about a half to three quarters of a kilometer on a local public road. In the morning we got up, and they would turn the lights on throughout the whole corridor when we left for the morning shift. They would tie us together with a steel cable...about 300 people. They locked it in the back. This was a farce and we called it a "Russian Bus." The worse was in winter, when we would walk at 4am across 40 centimeters of fresh snow. That was nothing to cheer about. Sometimes it also happened that someone would slip and the others would slowly walk over. On those occasions guards would start yelling, "Stop." Other similar stories would happen there.

So this was the way you walked to the Eduard mine?

Precisely. One day we would go there only to be told that we would be going down, and on another day I would have to go down the shaft and work like a normal miner...even though there were no instructions and they hadn't show us how. Then I was told that I would clean the gutters. So I would clean the gutters where the water was overflowing. Then I worked as a mine carpenter - I would repair the chimneys, stepladders, and so on. Then I worked with the bricklayers assembling the chimneys. Then my friend Husník told me, "Come with me - we will work as breakers." That was something like the pinnacle of the mining experience. While other breakers were breaking horizontally, but we would break into the ceiling. We didn't want to get any uranium, but there were quotas, so we would go and steal some ore from where the civilians worked. There, we would steal a small box of uranium stones, grind it, and then sprinkle it back on. The measurements would show that we did a good job right away. So we met the quota, benefited from it, and not only did we break stone, but we even had some ore. Yet, up in the grinder they couldn't benefit from any of this because it was wasted rock.

You told me that after two and half years you were transferred from Camp L to Nikolaj. Did they tell you any reason why?

No, they would never give reasons to anybody. I know that many of my co-prisoners switched from four to eight camps or prisons during five years of imprisonment. It depended on how they needed to place them. In the end - meaning, in the second half of the 1950's - they were also dividing us according to professions. In Opava, for example, they built offices for project engineers, and so some of us who had studied in various technical schools were taken there to start working for the Ministry of Interior. Also, if someone tried to escape, he would be transferred somewhere else or into a normal prison.

Can you remember any Communists who were in prison with you?

There was a guy named Pepík Just and he worked at one of the ministries. He was a member of a subgroup in the process with Slánský[10]. I also met Gustav Husák[11], who briefly went through Jáchymov and stayed for about three days. The Slovaks wanted to lynch him, but I told them that this didn't make any sense and that trouble would only come from it. And he left quickly anyways.

How were you finally released? Originally you were sentenced for seven years, but you went home in 1955. How did that happen?

According to the decree of the President Zápotocký.[12] In 1953, I received a written announcement that my sentence was being lowered to five years from the original eleven[13]. My prisonmates and even the guards were advising me to ask about a probationary conditional release. I refused to do that because if I agreed to do that I would have to cooperate with the secret police and communists to do that. I radically refused to do this from the first day.

How many times did you see your parents when you were in prison?

Well I remember that there were three visits for the whole duration of my stay - two in Camp L, and one in Nikolaj. There weren't any more.

In four and half years?

Yes, in four and a half years. I theoretically was able to ask for a visit once every six months. Every time I would ask though I would be placed in a cell or else they would make up some disciplinary punishment. After the first few months at Nikolaj, it took a while before my work efficiency shot up to 100% and prisoners under 100% were automatically denied the opportunity to write letters, have visits, and so on. So visits and letters were something like a reward for a good job. In camp L it happened that right before Christmas the Commander Šlachtecký would bring a whole amount of huge letters on a tray. It was snowing and a big wind was blowing. The wind blew, and all the letters started flying towards the fence that separated the camp from the surrounding and he said, "If you want your letters go and get them," but there was a threat that if we did the guards would start to shoot. So this was one of the ways of suppressing the number of messages from home.

However, I even had an illegal connection with home through Stěpánka Baloušková. When I wrote a letter, within two weeks - sometimes earlier - my parents knew what I wrote. They got the letter and would send an answer back. So I had pretty good information about what was going on at home;similarly, my parents knew about me. I was a friend with the future General Husník. We were together for two or three years at both camps. He had some experience because during the War he was in prison as well, and knew how to get in touch with civilians. Thanks to Stěpánka Baloušková, whose husband was a Brigadier Captain Baloušek, who Husník knew before our prison terms, we had contact on the outside. One of the civilian employees working in the camp mediated between us, and both she and Stěpánka and then sent the messages further inland. Within this group, Stěpánka was mediating mail for up to forty-seven people. Husník and I coordinated it. We were distributing and gathering letters. The civil employees in both camps helped with it.

How exactly did this secret postal system work?

We had to write on the thinnest kind of paper so that the the maximum number of papers could be taken at one time. Then we had to collect them all in a certain way and tell certain people whose turn it was. There had to be some kind of order to it, because we couldn't receive thirty letters at once. Each week there could be five to eight letters coming in. The letters were sent to Prague; and from there, distributed to Bohemia and Moravia as well. It wasn't just letters, because through the civilians we had the opportunity to buy some food, which was scarce. Families were also sending us normal civilian money and packages with the most basic necessities, which meant mainly clothing and shoes since these things were totally missing in prison.

How exactly did you contact civilian employees there?

Husník had the main contact in Camp L with the storekeeper lady. I only knew her by sight; I never even talked to her. It was easier on Nikolaj. Husník got in touch with civilian geologists and surveyors. These people were able to freely move in the mines, and so we were able to have contact with them. I knew the civilian geologist Míla Novotný, who has already died. The other one was Mirek Mikšovský. Up until today we are friends. When I was released we kept going on holiday together to our cottage in Říčky for twenty-five years. So it's a friendship that has lasted until now.

When looking at your family relations or the aspects of your imprisonment, how did your family view it? How did they manage when they had a nineteen-year old son behind bars?

It wasn't easy because my mom was a cleaning lady at the Regional Hall, and right after I was locked up she was fired, and they didn't want to give her a job anywhere after that. My father was a driver at the transport company, driving buses and tram buses. He was also fired a month later. He had to go through the new recruitment process. The worst was for my siblings, two sisters and a brother, who couldn't go to proper schools. All three of them had to go to trade schools. At that time my brother used to go to a normal secondary school, and there was one teacher, Mrs. Višňákova, who was terribly malicious. I know that once he had to stand on a platform for the whole hour. She would always turn to him and say "So this is the brother of the national trader and spy."

Do you have any "souvenirs" or things from the time you were in prison? For example, are there any pieces of silver or other things that you were sending to your family?

Yes, some of it remains. Husník and I were actually making things like that. Not just for us, but for other prisoners. From my prisonmate Bohouš Šesták I have two beautiful things he carved for me. One of them is a fully carved chessboard and pieces. The figures are about 2 centimeters high and the queen is about 4 centimeters. Then I also have a triangular ashtray. On this there is the carving of a symbolic Scout lily. And finally I have a little figure of a man. The Triangle is the sign of life; the figure of the man means us Mukls[14]; and the lily is the symbol of the Scouts' ideology, for which we were in prison. I was also putting pictures into plexiglass. I put in photographs of my family, which I later sent home. My sister still has one picture like that. We were also carving various objects from bones, or we would make little hearts from plexiglass and various other objects. I made tons of things for my prison mates. It was a hobby to relax...and it was also a petty clockmaker's job, because everything was so tiny and small. For example, there would be a little cross preserved in one of those hearts, or someone would chew bread and then make it into sandals and a sleigh. There were various ideas on what to do or create. I still have a lighter that the Mukls made.

When you first heard your sentence - that you were potentially going to prison for eleven years - what helped you struggle through that time when you didn't know that you could go home in 1955?

(Light laugh) It was our general belief that we would not sit there, hoping that something would happen and all that we started in this world would not fade away - especially after the execution of Dr. Horáková[15] or General Píka[16]. We didn't trust that this would be in a permanent state, or that it would last for forty years as it has. This gave us motivation. And we hoped that we would get out earlier and not really have to sit out the whole sentence. Many people were released on probation although they were in prison for ten or thirteen years. But there were a couple people with fifteen or twenty years who sat out their sentences to the end.

How did your rehabilitation and compensation turn out?

Right in 1989 we established the Confederation of Political Prisoners. I had first-hand information since I was one of the founding members and the head of one of the branch offices. When they started talking about rehabilitation in 1990 we immediately prepared everything for rehabilitation, and informed our members of the confederation, as well as the offices in Hradec, about the conditions of rehabilitation. There were about 350 people. In Hradec everything went all right. I personally got all the compensation that I was supposed to get.

What comes to mind when you hear the name Jáchymov?

A chill runs down my spine. Everything is fixed in my head. Unfortunately I sometimes have a dream that I am in a prison in Jáchymov. It's an overwhelming experience that I cannot erase from my memory or subconscious. Especially now, for example, that I found out that one of my friends that I made there has leukemia, and is practically fighting with death. These are the red threads that line my memory. He used to be a young person, but today he is written off because he has leukemia from the radioactivity.

Did you also leave with some permanent health problems or were you lucky enough that it went around you?

I had a few smaller injuries - broken fingers and ripped-off nails. That often happened at the workplace in L while we were handling barrels. Then I had two injuries in Nikolaj, and one of them was really quite a misery. I was carrying something when the ladder broke from underneath me and I fell down. I flew and landed on my back four meters below and I cut my elbow and twisted my shoulder. I crawled down the tower and there I gave a message for Husník that I was injured. In the infirmary they gave me first aid, put stitches in, and on Monday I was working again, even though my wound was seven centimeters long and very deep. So this is just an idea of how they took care of the working people in Jáchymov.

What did you think of the regime change in 1989?

I was happy that it was the end. From November 17 I was a little naive when I heard how many people ended their memberships in the Communist party. I thought that giving up the membership would solve everything. I later saw many people who used to be members of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and now they are in government or now have political functions. We weren't happy about this at all, and we knew that things should be improved. So we did everything we could to pass the Lustration Law.[17] This is our problem even today because we can see how even this law is not being followed, and people are getting around it in bad and nasty ways. We cannot agree when we see ex-secret police and informants sitting in the main leading positions of the state and elected positions. If the candidates invite us to give a public speech, whether it for local, parliament, or European parliament elections, we always have to make sure these people were never apart of the party nor cooperated with the secret police,. If they had something to do with the communists, we would not talk to them and we will not talk to them. At least in Hradec Kralove, we don't.

Is there anything you would like to tell to the young generation of today?

Find your goal in life and go and get it until the very last breath. Nothing else. Let your health and perseverance help you.

Thank you very much for the interview and I wish you a lot of health and success.

Thank you also and I hope young people will understand this because we do it for them. We don't want to cry because when we have struggled until now. We will have to struggle until the end of our lives. But if we can, we want to give them the information, because no one will give it to them later on. They can get such genuine information from us. A film can be very much distorted, and it doesn't represent reality in its true nature. Some movies were done very well, but they were missing the thought process - the inner feelings that only we can give to it. The feeling of family solidarity, because in civilian life, the family was sometimes affected more than we were in our minds. They weren't locked, but they had financial and health problems - problems in how to make a living - if we didn't have this family solidarity, I don't know whether we would have survived in prison.

Thank you very much for the interview.

[1] Hradec Králové- A town in northeastern Bohemia.

[2] In May 1938, military intelligence became aware that the German army was moving in towards Saxony and Silesia along the Czechoslovakian border in imminent preparations for an attack on Czechoslovakia. In response, President Beneš set up a partial mobilization; meanwhile, Hitler was holding negotiations with Chamberlain. Without the consent of Beneš, the British and French governments agreed to appease Nazi demands. The decision was reached on September 21, 1938. The Czechoslovakian government issued a decree of general mobilization two days later. By September 28, 1938, the signing of the Munich Agreement ended this attempt as well.

[3] Czechoslovakian Scout and Guide Federation- this founding Member of the World Organization aims to encourage the education and self-education of children. Although established in 1911, the Scouting had been prohibited two times by invading regimes - the Nazis and Communists. Many Scouts, alumni, and Troop Leaders either died for their acts of civil disobedience, and many of the remaining Boy Scouts became victims of the show trials in the 50's. During periods of political freedom, such as in 1945, before the Communists' invasion; in 1968, during Prague Spring; and finally in 1989, after the Velvet Revolution. In 1996, the Czech Republic was accepted as the 141st member of the World Organization.

[4] Pardubice- A town approximately 26 kilometers to the south of Hradec Králové.

[5] 1946 Parliamentary Elections- The elections won by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

[6] The Czech Confederation of Political Prisoners (KPC)- established January 3, 1990, the KPV represents the confederation of the Czech Republic's political prisoners and association of all political prisoners from former Czechoslovakia.

[7] Camp L- Also called also a "liquidation camp." Camp L had a "Tower of Death" where prisoners came into direct contact with radioactive uranium.

[8] By uranium ore we mean pitchblende mined in the Jáchymov district for scientific and military purposes of former USSR.

[9] The Tower of Death- A uranium-processing tower which still stands close to Jáchymov in northwestern Bohemia.

[10] The Slánský Trials- These political show trials prosecuted individuals from all segments of society, including key members of the Communist party. The leading communist investigated was Communist Party's Secretary-General Rudolf Slánský and, from 1950 onwards, the state secret police concentrated on "searching out the enemy even among its own."

[11] Gustav Husák (1913-1991)- President of The Czechoslovakian Socialistic Republic from 1975-1989. In 1950 he was accused alongside with V. Clementis, L. Novomeský and many others for "bourgeois nationalism." In February 1951 he was locked up, and in 1954 sentenced for life imprisonment. Husák was among the very few who refused to confess - a factor which most likely saved his life. Internally, he remained a believer in Communism. He was pardoned by President A. Novotný in 1960, and fully rehabilitated in 1963. In 1969 he became a leader of the Slovakian Communist Party, and proceeded to help Russia reverse the liberalism. By May 1971, he would become General Secretary, and in 1975, the President of Czechoslovakia.

[12] Antonín Zápotocký (1884-1957)- Czechoslovakia's Prime Minister from 1948 to 1953 and President of Czechoslovakia from 1953 to 1957.

[13] May 1953- A month in which 15,379 prisoners were released on a pardon. This pardon also referred to 4,035 prisoners from the uranium labor camps.

[14] Mukles- A slang term for inmates who knew they would die in prison. The word "mukl" is derived from the abbreviation of "muž určený k likvidaci" or "a man on death row." At first this label specifically dubbed political prisoners issued life-sentences by either Communist or Nazi regimes, but later it would refer to all political prisoners.

[15] Dr. Milada Horáková- (1901-1950)- A Czech politician executed during the 1950's show trials for putative conspiracy and high treason. Although televised, she refused to follow the trial's script. Among others, Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, and Eleanor Roosevelt had petitioned for her life.

[16] General Heliodor Píka- (1887-1949) A Czechoslovakian officer executed in a show trial primarily for liberal attitudes demonstrated during his WWII mission to the Soviet Union.

[17] Lustration Law- A set of laws considered by post-communist countries which would limit the political and military participation of ex-communists.