Květoslava Moravečková

Interview with Květoslava Moravečková

"What helped me most was that I was myself and I didn't take the others into consideration. My mind was always at home." ~ Květoslava Moravečková

Interviewer: Klára Pinerová

This interview's English translation has been gratefully edited by Ms.Olivia Webb.

I'd like to start with a question about your childhood. Where did you grow up and what are your memories of your parents?

I was born February 10th. I was the only child and my parents were very kind. My mom and dad would do anything for me. I went to school in Malín[1] and I had quite good grades. In Malín there was an elementary school that I attended for four years. Then I passed entrance exams to Vlašský Dvůr secondary school and stayed there for another four years. My family had farmland, about 12 hectares, and we also farmed a field that my uncle owned so that we had enough for the cattle. Altogether we had four cows, a heifer and a few horses. My family was Czech and my granddad always taught me Czech songs. My granddad and my dad could speak German and Czech perfectly. I was supposed to go on an exchange program[2] to learn German, but unfortunately it never happened because the war started. Before the war started I had gone to a training college for nursery school teachers in Křižovnická Street opposite the Parliament[3] because I had always wanted to bring up small children.

Did you farm your land by yourselves?

My mom had a maid, Kristýnka, and she helped with the household; and we also had a house that we used for accommodating farm workers. These workers helped us with work and of course got paid for it. Yet we were cottagers, and my father never pretended to be a farmer – although in reality he was a farmer through and through. We also had two women working for us and they did the hoeing. Sometimes my auntie from America came. Auntie wrote for the journal Ženské Listy [Women´s Papers] in America and for the Hospodářské Noviny [Economic Newspaper] also in America. One time a woman called Mrs Pavlíková, who also wrote for Ženské Listy, came with auntie. They both knew Alice Masaryková, the daughter of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk[4]. In America, there was an organization called the Czech Ladies Association, a member of which was also Alice Masaryková. Alice was always telling them to stop by at Lány[5] when they come to Czechoslovakia. Once when my auntie and Mrs Pavlíková did go to Lány, they took me along. I was about ten years old. They dressed me up fine and off we went. I will never forget the meeting with President Masaryk. I see it as clearly as if it was today. He came riding a horse, nimbly jumped down, handed the reins to the groom and bowed for the ladies. I remember auntie telling me that I must not greet the President ‘Ruku líbám!' [Kissing your hand Sir.], but I must tell him, ‘Nazdar!' [Hi!] So I told him ‘Nazdar!' [Hi!] and shook his hand. He replied, ‘Nazdar!' [Hi!] . I still like to recollect the meeting even today.

Which political party did your parents lean to?

My father was not a member of any political party, but during the First Republic he tended to lean towards the social democrats. For example, he liked Masaryk more than Beneš[6] or Štefánik[7]. He was held captive by the Italians during the First World War and he was telling me about Masaryk, Beneš and Štefánik coming to Czechoslovakian soldiers and trying to persuade them to join the legions[8], but some of the soldiers were wounded, for example my father was shot in the leg, so how could he go and fight? But Štefánik came and addressed them, ‘Brothers, this is the situation we have and those of you who can, please join the legions, but we don't want to put any pressure on you.' However, Masaryk and Beneš did put pressure on them. My father didn't join the legions in the end. With him was a man called Brychta, also from Malín and he used to bring bones for my father to crush and make into soup. However, news spread, and Brychta didn't get away with it. My dad used to tell him then, ‘Brychta, if I ever get back home and slaughter a pig again, I'll invite you for every single pig slaughter I do.' And so he did. Every time we slaughtered a pig, Brychta came around and helped my father.

How big actually was Malín? How many inhabitants or houses did it have?

There were 25 houses altogether. The wealthiest farmers were Zedník, Pokornej, Vlk, and another Pokornej. Us, the Zima family, the Fuchsa family and our neighbor Filip were, I would say, middle farmers.

Did you feel any changes around 1938? What was your experience with the establishment of the Protectorate?

We, in Central Bohemia, didn't really feel any changes. However, we had relatives in the mountains, and there it was a totally different situation. I used to go there as a child, but later, people had to have a special permit to go there and I, as a child, didn't have it. I only had a Kenncard. Every time I came there, Pepík Hnyků, who was a clerk, would take me to do the cheese delivery with him. He used to say, ‘Květuška, we will take the car and do the cheese delivery and we will go to the Sudetenland[9].' I didn't have the permit, so I had to crouch and Pepík could speak fluent German, so he would tell the SS officer, ‘Das ist meine Schwester' and handed him a cheese, so it always went smoothly.

What was Malín like during the war?

Aircraft flew over and bombarded Kolín and bombs flew over our heads. Once we were slaughtering a pig. We did it on the sly and it was illegal. We had an electric steamer and they cut off electricity, so we couldn't cook the meat. Mum lit the stove quickly. It was Velebníček who slaughtered the pig that time and he said to my father, ‘Calm down, Mister, if someone comes, we will just say that I came to take care of the piglets' teeth and it will be fine...' In the end we managed to finish anyway, the blood sausages and everything... and we had a jolly good feast.

Did you have to pay taxes to the Germans?

Yes, we did. We paid in kind. Eggs, for example, but I can't remember anymore because I was just a little girl. I remember that we had to hand in eggs because once my aunt, my mother's sister, came and my mom had promised to give her some eggs, but my mom used them for paying the tax, so she had nothing to give her and aunt scolded her. Mom said, ‘I'm not going to let them give me a fine just because of aunt.' She came for the eggs a week later.

Were there inspections?

If some inspectors came, my father would start speaking to them in German and it would be OK. We weren't friends with the Germans, we were Czechs, but my father was more a Slovak because he loved Štefánik. For one, Štefánik was a protestant like we were and second, he didn't try to persuade them.

Can you remember the liberation?

They shot about 9 to 12 people here who are buried here in Malín. Germans shot them when they were retreating. I don't particularly like Russians either. They were too familiar at the beginning, but they were also a bit aggressive.

Do you recollect the post-war period?

After the war I became a teacher in a nursery school and stayed there until the time when I was arrested – until the communists got me – and that was it: my life was ruined. I divorced my first husband because he was a communist with every bone in his body and I was not. Then, when they arrested me, they brought me to Kutná Hora, the same place where Havlíček Borovský was imprisoned. I remember wondering to myself, ‘In which of those cells could Havlíček have been locked up?’

Why did you get arrested?

Because we kept an informant in our house. I barely knew him because I was working then and when I came back he was gone. My uncle, Mr. Žďárský, brought him to us. His name was Němeček and he said he was cooperating with America. He stayed for about two months. You know, they were so good; my family would die of hunger to feed other people. My parents had a heart of gold and they always gave to beggars. Němeček was arrested later and so was everybody who had something to do with him. We were pro-American because we have relatives there and perhaps that's why my father believed him. We really didn't think twice about it. We didn't know that they would make such a monster-trial out of it and one thing that never, ever crossed our minds at all was that we could end up in prison because of him. Lots of people from Malín got arrested because of him.

Can you describe your arrest?

We were arrested in one day, my father and me. Father was arrested in the morning and I in the afternoon and we were both arrested at home. I did some training in Kouřim at that time and there was a rumor that people were being arrested. We were all shaking with fear. When they came to arrest my father in the morning I was in Kouřim, but I faked being ill. I got home in the afternoon and then my mom told me that my father had been arrested. Eventually, in the afternoon, they came to take me too. They came and said, "You'll come with us. We want to ask you some questions!" They had to show me their ID and they took me to the district council. That was when there were lots of arrests going on in Kutná Hora and they were starting to arrest people in Malín too. I really didn't know at all why I was being arrested, but I had a clue that it could have been because of Němeček. They took me for questioning at the Kutná Hora district council, but I denied everything. I was arrested on February 7, 1952. My trial was in May 1952. I was sentenced to ten years, got a three-year pardon and was released on February 7th 1959. My mom kept asking for sentence reductions during my time in jail.

Can you describe the interrogation process?

It was relatively calm. They weren't being really aggressive and they didn't use swear words neither. They accused us of knowing Němeček. I didn't deny it because he was a husband of my schoolmate. Then they locked us up in a prison in Kutná Hora and I remember the freezing cold weather that day. The jailor took everything away, even my coat. I had a skirt and they gave me stockings that kept sliding off my legs. They also gave me pieces of string and I didn't know what for. The string was to tie the stockings and hold them up. The jailor was incredibly stupid; she couldn't even spell the word "cigarettes" correctly. With me was a retribution prisoner[10], Ilona Hofferová, and she was trying to calm me down when I started to swear and told me that woman was a chief officer. I had a golden watch and it was stolen. When I think about it, there were many things I never saw again. So they didn't beat me or anything in there, but after the trial they brought us to Pankrác, where it was catastrophic.

Could you describe the cells in Kutná Hora a little bit?

There were about four of us in our cell: Mrs Königová, Hofferová and one more. It was a dreadful place. There was a "šajzák," a washing pot, where we went to relieve ourselves. It stank disgustingly. We had beans for lunch – that was a nightmare – and then we had potatoes but we never got meat with them. When they were taking us to the monster-trial, my father gave the jailor sugar to give to me. He believed in sugar the same way I do. The jailor told me, "Missus, when you are eating potatoes, watch out – you have something here from your daddy." Dr. Motejl helped me in a similar way when he was employed as a doctor for female prisoners. About two days before the trial, the jailor brought me some glucose: "The doctor sends you this. He says you should eat it. It's nutritious." The jailor we had there was good. Glucose is also good for your nerves. First, they gave us white ribbons – those were for district prisoners – but then before the monster-trial, they gave us green ribbons. Mrs Königová told me that we would have a trial at the state court. Her husband was executed and she gave me a small loaf of bread before the trial started. I went to the trial thinking that I would be released. I had no idea that it would end up the way it did. I was certain that I wouldn't stay in jail for long. In the end I served seven years out of ten.

I'd like to go back to your trial. Can you remember the proceedings?

During the monster-trial, they were feeding me. It was just a bit of black slurry and a piece of bread, but my father, for example, didn't get anything at all. However, I will never forget the potato soup. It was nothing special, but we got a scone with the soup. I said, "Commander, could I send this scone to my father please?" I was allowed to, so I sent it to him. They just gave them absolutely no food at all, and my father had had a stomach operation.

I shared the cell with Mrs Königová, as I said before. She told me, "Květuška, when you are before the court, you tell them everything." That's why I wasn't afraid of them. She gave me support that I needed so much. They tried to throw shame on America, but I told them, "What do you know about America, have you been there? It's true that I haven't been there, but my relatives live there." That's what I told them in front of the entire court hall. There were many workers from factories in the neighbourhood and the hall was completely full. I felt sorry for my father, first and foremost, but he wasn't afraid either. We just didn't want to play the inferior and the humiliated. The trial was in a local public house in Malín, the same place where theatre plays used to be put on. On the stage, all the people of the village were sitting. We were supposed to be judged by prosecutor Čížek,[11] but he renounced the job. There were twelve people to be judged. I knew almost all of them; they were people from Malín: Holec and his son, Havelka, Eliška Štípková, my father, me, the postman, whose name I've already forgotten, and I can't remember the rest either. I remember Holec declaring, "Ladies and Gentlemen, I do not see this as a trial. This is a theater play." The trial lasted one day and the sentences were: 10 years for me, 12 years for my father, the same for Holec and 12 years for his son too, I think. The sentences were severe. Eliška Štípková got the least severe sentence because she was a sister-in-law of that informant rat Němeček and she only got one year. Němeček wasn't put on trial with us. If he was put on trial somewhere else, I do not know, and we never saw him again after that. He was said to get a good position and had some kind of a hotel some place.

My uncle, who introduced us to Němeček, had a trial in Kutná Hora in Tyl's Theater. They loaded us into vans and took us to Pankrác[12]. I sat next to my father and he told me, "Květa, I'll give you a slice of bread because the bread in Pankrác is terrible and you will not want to eat it." That was the last time I saw my father until my release from prison.

Can you remember your arrival at Pankrác?

When we arrived at Pankrác, we had to stand facing the wall and put our hands up. I was terrified they would shoot us. When I went to the hospital for a check-up later, I fainted there. There was a doctor or “mukl”[13] sitting next to me with a wet towel in my face and he was telling me not to be afraid because he was a “mukl” as well. That was my first time in prison and I had no idea what the word ‘mukl' meant. Then they put me in the cell with Eliška Štípková and we went to beat the carpets for the SS officers. At that time, I was stupid enough to give them a proper beating.

And where did they take you from Pankrác?

From Pankrác they sorted us into units or so called "commandos." I got transported to Jilemnice and it was a nice commando. Although it had a wet hall, it was fairly good there. I had relatives who owned a grocery shop there. We used to take a cart and do shopping for the kitchen. We always went with the jailor, of course. They always gave me butter, fruit and vegetables, so we were fine. The officer had a good time too, because every week he would walk away from the shop of my relative Mr Tuž, with a case overflowing with fruits and vegetables. When they found out we were relatives, they banned me from going shopping. I didn't even thank them for helping us so much, but I was worried because they constantly tried to get me.

What work did you get in Jilemnice?

We spun linen and put it onto spools. We only had one shift and worked about 8 hours. Then we went to the camp and had something to eat there. Then it was time for lights out and we went to sleep. We were patrolled by factory people. Later only 12 of us remained, but I must say that the staff officers were really nice to us, the real political prisoners, and we had cocoa and sweet buns. We stayed there together with the regional prisoners and we lived in the same block, but each group had a different room. Once, when we were walking to the factory, a bus appeared all of a sudden and one inmate jumped under the wheels. She was a murderer. A day before she came to me and said: "Mrs Vosátková, do you believe in life after death? For I had a dream that my husband, whom I had killed, came for me." After that she was just sitting there doing nothing, lost in thoughts. The problem was I couldn't give her any answer, really, and the following morning this thing happened. There was chaos and we were asked whether there was a doctor amongst us. Lída Krupičková was and said so and she escorted her all the way to the hospital. Later, she told me, "Květa, I shouldn't have gone there with her. It was awful." During that week I had visitors and my mom learnt that a prisoner had jumped under a bus. My mom was upset because she was worried that they were treating us badly. From Jilemnice I went to Minkovice and from Minkovice to Varnsdorf and then through Pankrác to Zlín and from there directly to Želiezovce. From there I went to Pardubice in 1956 where I stayed until my release.

From Jilemnice they transported you to Minkovice and that was perhaps a smaller commando. What do you remember about it?

In Minkovice we abraded stones and I enjoyed that work. It was an easy job there. In Varnsdorf we wove nylon. That was in 1953. The directors came and chose big, handsome girls for the night shift and I was one of them. During the first night shift I was very sleepy. There were machines as big as my house and I switched them on, all spools, sat down on a box and slept. All of a sudden the overseer came and said, "You only had six spools on. Switch on the whole machine." I woke up and walked sleepily to switch on all spools and went to sleep again. I did very little work then. From Varnsdorf I got transported to Liberec. The prison van came and I took all my things. In Liberec I got a two-year pardon. When we arrived, the overseer came and asked us, "Girls, what's the court you've been sentenced by? By the state? Do you like tripe soup? Two pots full of thick tripe soup and a half-slice of bread for everyone. Supervisor!" We were all caught by surprise, we were starving because they didn't give us enough food in Varnsdorf. Then the escort came and we went off to Pankrác where I collapsed – and that‘s why they made an X-ray in the Pankrác hospital. They found out that I was catching tuberculosis, but I had no TB, just weak lungs. From Pankrác we left by bus. We had to wear civilian clothes so that nobody could see that they were transporting prisoners. We drove around my home and I saw our house and tears went down my cheeks. I was saying to myself, "Mom, I wish you could give me just a piece of bread crust." Later, when my mother came to see me, she was telling me about this dream she had that I came to knock on her window and ask her for a piece of bread.

Where were you transported?

We came to Zlín, which stank unbelievably of rubber. All food stank of rubber. We worked at the assembly line and each of us had her own task to do. I felt sick all the time and the foreman saw me and I went to the doctor's. The doctor told me to stop working at the line immediately. I was happy that I didn't have to be in the stench anymore. Then they closed it down and we got transported directly to Želiezovce. When we arrived, they divided us into quarters. The following day there was a line-up and we were assigned various jobs and I was lucky. I got a job in a place called "járek", where the disabled worked with us. We went to work by a small handcar and I worked in the tobacco gang. It used to be very hot there.

You said that you worked together with the disabled?

Yes, poor souls! They were mentally disabled and if you saw how they were treated! They were treated like slaves. They got up in the morning just like us and they got black slop. They got a piece of bread and went out to work into the scorching sun and each of them got a line of beetroot to hoe. A supervisor was following them, with a long stick in his hand, watching how everybody worked. If one of them didn't do the hoeing properly, the supervisor took the stick and the disabled had to go back. They were so scared of the supervisors, poor souls! It was unbelievably drastic. This was how socialism looked like.

What was the arrival in Želiezovce like?

When we came to Želiezovce, it was snowing hard and the weather was freezing cold. I wouldn't wish this on anybody. It was snowing and raining and we were walking through corn fields. All was wet. We came to our quarter and there was a small stove to be shared by 40 people. In the morning our clothes were still wet as we were putting them on. It was slavery! We got a small bucket of coal but ended up using corn for fuel anyway. The accommodation was awful because there were bedbugs all over the place and we had to kill them every night. We lived in sheepfolds – they were a kind of wooden houses. There were large rooms that slept about 40 people and each of us had a bunk bed. There were normal houses as well. Nuns and prostitutes lived in one of the stone houses.

Can you remember the hepatitis epidemics?

First there was a typhus epidemic in Želiezovce. They were supposed to give us vaccination and I was afraid of it. I remembered my father how my father told me that they got typhus vaccination during the War as well, but he was telling me, "I always squeezed it and there was a squirt of blood, but I was able to bear the vaccine better than the others." The doctors came first and they were supposed to vaccinate us, but then they only left the vaccines behind and left. One ampoule was supposed to be for two or three prisoners. The woman who gave us the injections was not a doctor at all; she was a kind of backstreet abortionist. There was a line-up and I came forward and said, "Officer, I would like to report to the chief officer because of the way you give us the vaccination here, we don't even give it to our pigs at home." I came to see the chief officer. We had to report ourselves like soldiers do, "Prisoner number such and such reports arrival." I told him I was not going to get the vaccination. He replied, "Ok, I will tell the doctor to boil the needle and use a new ampoule for you." I was on cloud nine because I expected he would send me to a correction cell. As soon as she gave me the injection I squeezed the spot. Later, doctors from Pankrác arrived and said it wasn't typhus but hepatitis. We were to get Gama globulin and again they had to boil the needle for me and open a new ampoule. There were prostitutes and who knew what kind of diseases they could have had.

In Želiezovce did you get to know, for example, about the Hungarian uprising?

Well, once, when we were on our way to work, and we heard distant sounds of shooting. It was close to the Hungarian border. The supervisors told us to ignore it because it was from the marvel mines. However, we knew already that it was the revolution in Hungary. The following day, when we were going to work, there were soldiers everywhere. We arrived at the yard, lined up, and got divided into the state and the regional prisoners. We, the state prisoners, were put in quarantine and weren't allowed out anymore. We were issued a three-liter bottle of milk, tomatoes, peppers, better bread and bigger food rations. We didn't work; we just caught bedbugs. And then they sent us to Pardubice. I was happy because I thought that it would be closer for my mom to come for a visit and she wouldn't spend so much money on traveling.

How often did you mother visit you?

Mom went to see my dad as well, and she didn't have so much money either. She came to see me in Želiezovce one time. I had no contact whatsoever with my dad; we didn't even exchange letters. In the end we met only when I was released.

Was it a problem to communicate with murderers and prostitutes?

Not with the prostitutes, no, but it was with the murderers. Some of them were sadists and had no feelings. I used to study characters and people in prisons. I met all sorts of people there. In Pardubice there was a gypsy woman who used to come to see me. She couldn't read and she got letters from her child, so I used to read them for her. The jailors didn't like gypsies, and were aggressive to them. They mixed us; for example they put nuns together with prostitutes just to humiliate them.

How was your arrival in Pardubice?

We arrived and I got a job at the garment factory, but I didn't like it there. The quotas were too tough. Lída Krupičková assigned the easiest jobs to enable me to meet the quota, but I couldn't manage anyway. On New Year's Day there was supposed to be an announcement of who failed to meet the quotas. My name was announced and the chief officer came to see me in the garment room and was asking me why I wasn't meeting the quotas. I replied, "Officer, I came from Želiezovce and I can't do any more." He said, "Would you like a lower quota?" However, I never told them when I needed something from them, so I told them that it didn't matter to me. The Tesla factory in Přelouč was just being opened there. There they trained us to do potentiometers. It was better there and then I worked slowly so as not to increase the quota.

Were there sanctions for you for repeatedly not meeting the norm?

Yes. For example I wasn't allowed any parcels when my mom came to see me when I had a sanction. My mom was sad, but on the other hand, I was sometimes glad because I knew that mom had very little for herself sometimes.

What did you wear?

In Želiezovce we had skirts and white men’s shirts with no collars. When it was very hot in there we pulled them out so we could have a bit of air circulation around our bodies, but we weren't allowed to wear bras. In Pardubice I got trousers, a coat and a shirt, and it was all made of itchy cloth. We all had the same tog-brown or grey-brown. We also had square black grey scarves. Our underwear was provided by the prison as well. They changed it for us every week but I used to hand wash it to keep it clean. I put it over the frame of my bed and sometimes the other inmates got angry because of that. Well, it really was an ordeal sometimes. They never changed the rest of the clothes for us. When we came to the camp, we got two blankets, a bolster, and that was it. There was a straw mattress and that's how we made the beds.

Could you briefly describe what was the daily routine like? When was the wake-up call? What were the working hours? When did you get lunch and when did the lights go out?

In Želiezovce we woke up at six every morning, had breakfast; the first line up was already at seven o'clock. We were divided into work gangs and we went to "járek." My workplace was a bit further. We picked tobacco there and put it on long bars. The bars were later hung in drying house. Then we picked tomatoes and I used to eat them on the sly. The food wasn't great – only watery soup with a bit of hulled barley in it and bread. They brought us lunch there. We got lunch around noon and we worked until three or four o'clock, and then went back to the great yard by handcar and there was the general line-up. The line-up was usually around six or seven o'clock, and it lasted about an hour or an hour and a half. I can't tell you precisely because we had no watches. We could only tell the time according to the sun. If somebody ran away – as, for example, Dáša Šimková[14] once did – the line-up was longer because it took a long time to count us and find out if and who was missing. After the line-up we went straight to bed. We were glad that we could go to sleep. It was real slavery there! In Pankrác, it looked like this: In the morning we had to empty the shit pots and there was a revolting smell from them everywhere. Then we got bread and disgusting tea, it was a wish-wash really. At noon, some of us worked, so they took them; for example we beat the carpets and other prisoners could sit down, but couldn't lie down. Some of them had to walk around without stopping. In Pardubice we got breakfast in the morning, went to the garment room, and did sewing there. I was never able to meet the quota 100%. We got some wages for the work we did and could treat ourselves and buy something with the money. We worked until two o'clock and then we went for lunch, which we could take with us to the dorms. Around six o'clock there was the evening line-up and we went to sleep.

Did you ever have any free time? What did you do then?

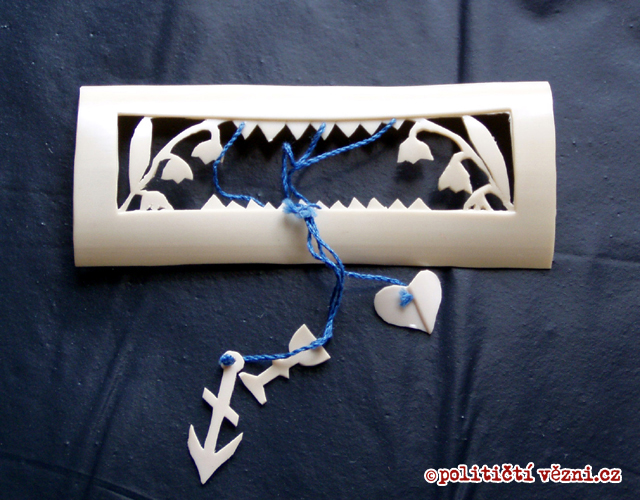

For example we did various kinds of handiwork. In Varnsdorf we made flowers. We begged for pieces of fine wire off the electricians and wound them around a pin, and then we took the wire and wound some yarn around it. I have a flower like this at home. My mom secretly smuggled it from the prison for me. It is a bit out of shape though, because when my mum came to visit, we shook hands and I had the flower hidden in my hand. Luckily, nobody realized it; otherwise I would go into solitary confinement as a punishment. Or sometimes we got lemons in a parcel, so I made a piglet out of it. Or we used to cut bookmarks out of toothpaste paper boxes, and we made different things out of bread too. That's why I wasn't interested in doing board games such as "Člověče, nezlob se!" [a table game "Man, don´t get mad!"]. Some even did chess. My dad, for example, had a wallet for camp money made out of toothpaste that I still keep at home.

Was it possible to borrow books from the library?

We could borrow books, but they were only socialist books and I didn't read them. We could borrow newspaper, but only the newspaper Rudé Právo[15]. I remember reading the paper once. The thing was that after finishing our own work, we had to do another job – we had to help the builders. I used to run away to the toilets because they couldn't go there to get us. Once he came, though, and caught me reading the paper. When a jailor came to the dorms, we had to stand up and report ourselves just as soldiers do during their military service. By that time it was shortly before my release and I was thinking he could as well bugger off. He came and I was sitting by the window when he said, "Don't you know what you are supposed to when an officer comes?" I got up very slowly, "I am very sorry, officer, I did not see you as I was reading the paper." He continued, "Which is your bed?" He took my blankets and threw them on the floor. Of course, we had to have our beds made the military way and when he was leaving, I said aloud, so that he could hear me, "I hope he doesn't think I am going to make my bed before the line-up!" However, I had to do a second job in the building site. We carted bricks. I used to go and take one brick, put it in the wheelbarrow, take a rest, take another brick, put it in the wheelbarrow, take a rest. The jailor shouted at me to work faster, but I ignored him.

What was the hygiene like in prison? For example, how often were you allowed to have a bath?

There was no hygiene. When we came back from work we went to the washroom, which was for about twenty people. There were troughs full of water. The washrooms were dreadful and I wonder how come I didn't catch anything serious in the prison.

Was there a supply of toiletries, such as toothpaste or soap?

This we had to buy with the "treat" money, with the camp money. I had very little when I was working at the garment factory. In Tesla we could have up to 80 Crowns, so I used to give some of it to Terezka Vejsadová who had a job stringing beads and earned like five crowns, which was barely enough to buy the toilet paper. I gave her a bit extra, so that she could buy other important toiletries. She was older, so she didn't have to buy sanitary napkins. She was like my mom. She was unhappy when I was leaving and she was staying. Her son had emigrated abroad and her daughter used to come to visit her. They also confiscated all their estates. Anyway, in the canteen we could buy sugar, biscuits, toilet paper, sanitary napkins. Chocolate, tinned food and other goodies were not available.

What was the food like in Pardubice?

In Pardubice we most often had potatoes and carrots, carrots and potatoes. It was very bland. The sight of carrots used to make me sick for a couple of years after that. In Želiezovce we picked peppers and tomatoes in the fields because the food was dreadful there. The soup was water and a small piece of bread and we were starving all the time.

Would you be able to describe the difference between a stone prison and the so-called "commando"?

In prison a jailor came and stuck a pot of coffee, or soup or some food through the door window and closed it again. Then I just sat on the straw mattress, but that was forbidden in some places. In a commando it was a bit freer; we could move around as we wanted. Despite being a stone prison, Pardubice was better in any case. It is true that the food there was also terrible, but we were warm. However, in Želiezovce we had to work in foul weather, sleet and frost.

You said that you met a retribution prisoner, Mrs Hofferová, in the Kutná Hora prison. Did you meet other woman prisoners who were sentenced according to the Retribution Act? What were the relations among you like?

I have to say that they wished for us to be imprisoned. Mrs Königová, who tried to familiarize me with the realities of prison life, told me, "Watch out for Ilona Hofferová. She cooperates with the jailor and is an informant."

Did you know also in Pardubice, for example, which one signed the cooperation documents and started to give information on people?

No, we didn't know because there were far too many of us. That's why I was always alone in the prison: I didn't trust anybody. I was alone, alone with my thoughts, and thinking about my mum and dad.

What was your release like?

Well, I wrapped all my things I owned into a blanket and had to hand in all things I got from the prison at the sick room. When I was leaving I left my camp money to Terezka and a kilo of sugar to Johanka[16]. At the sick room, I got my civilian clothes. I left for home and the girls stayed. The jailor took me to a small gate, behind which inmates unloaded coal. My father, who came to meet me there, told me, "Look, they are saluting you." My father came; he had been at home for almost a year, and had been released after serving half of his sentence.

What was it like coming back home?

When I came back, people avoided and turned their back on me. I lived with my parents, but an informant was sent into the village. Her name was Kučerová and she would eavesdrop on us and send the information further. She could do whatever she wished in the village. Once, her husband broke my arm. They planted them here when my mom was here alone. They stayed until I got married. Not only us, but everybody feared them. It was like living in a second prison. When I came back I went to the job centre and said that I was looking for a job, but commensurate with my education. So they told me, "We can offer you Mira, where you could do sewing or the state farm or the brewery." I applied for the Mira job; I left my ID there and was supposed to pick it up two days later. However, I had had an argument with Kučerová before then, and so she made it impossible for me to get that job. So I went to work in the brewery, but that was no good for me because my nose kept bleeding and I was wet all the time. So I had to go to work in JZD[17] (Unified Cooperative Farm) in Sedlice. I wanted to work in the garden, but after about two weeks the administrator Mr. Medřický came and said, "I am sorry, but I cannot do anything else except send you to work in the field with the rest of the women. This work is too posh for you." So I started to work in the fields. Once, on my way from work – that was the season for hoeing potatoes – the administrator ordered me to take a basket full of potatoes. I really appreciated it at that time, as we were quite poor. When I returned I didn't even have a bed and had to sleep on the floor.

Did you have to report yourself after coming back?

When I came back I got an invitation to come to the secret police to get my ID, as I didn't have it. The policeman told me, "Sit down here and wait for the superintendent." He came and told me that he would like to have a word with me, "You could cooperate with us and get various privileges in return..." He was telling me all this and I replied that I would think about it, but was saying to myself, "I don't give a damn. Me, cooperating with such rubble? You took everything away from me: my health, my property, and I will cooperate with you on the top of this all?" Later, I didn't sign anything and as a consequence didn't get a better job.

How did the people in the village treat you?

That varied. For example, when my father came back from prison, my mom didn't have even a potato, plate or spoon. So my dad took a basket and went to see a farmer who he had once helped when his farm had caught fire. He went to him thinking that he wouldn’t want anything for free; that he would pay for everything. The farmer told him, "I'd rather give it to the pigs!" Some people behaved towards us as they would towards criminals, but on the other hand, some of them were helpful. Once my father told me to take money and go to Mr. Linek to buy carrots, lettuce and onions and Linek told me, "Keep the money and off you go. Don't tell anybody that you got it for free." It was terrible. All of a sudden I was a beggar, and all of a sudden we had nothing. I used to go to the dairy shop and I wanted to buy a 200g piece of butter because it was cheaper, but then Mrs. Poláková winked at me and told me to wait a minute and gave me two pieces of butter for free. I went to the butcher's and they had a beautiful pig's head there. Mrs. Míškovská told me then, "If you want, I could give you a pig's head like that every week with the chin fold as well." And she did so. I was happy because I was able to get a big and good lunch for very little money. I came home and started to cry. We used to be a respectful family and the communists turned us into absolute beggars.

What happened to your estates?

JZD took the fields and at that time we only kept a few hens. We had an administrator appointed by the state and later they sold my estates for building sites. The whole of our garden. It was the worst part for my father – he couldn't bear it when they started to parcel out our garden.

Did you speak to your parents about prison?

Never, not even with my father. We both had our own experiences. When he came out of prison, he had frostbitten feet. I told very little to my second husband. I didn't keep in touch with the girls either because I was afraid.

Did you take in the events of 1968?

That was when the Russians invaded here. I was working at Skalka. Mr Zahradník took me there and he worked for Kopřivnice. He wasn‘t supposed to take me there because I was not reliable, but he took me there anyway. I was working with Mrs. Plačková. My husband repaired the house of the Bruner family from Prague and we would put them up for the night. I went to work at five in the morning. I met Mrs. Macháčková at the cemetary wall and she told me that the Russian had invaded here. As quick as a shot, I rushed home, woke everybody up and said, "Switch on the radio – something is up." We switched on the radio and I didn't go to work that day because I was scared. We saw tanks going by. I stayed at home for two days and fortunately it was not a problem at work.

What did 1989 mean for you?

I got a pension, my mother and father were gone, and so I couldn't speak to anybody about it. I welcomed the fall of the communists, but still didn't trust the whole thing. Now they are getting more power again.

The life in prison must have been grueling. In Želiezovce the work was extremely hard, and on top of that, you were sentenced unjustly. What helped you to survive the years in prison?

What helped me most was that I was myself and I didn't take the others into consideration. I had my mother and my father and kept thinking about them all the time. I protected my health and that was important. I didn't really make any friends and just kept imagining what it might look like at home. My mind was always at home. I would never move into some kind of hotel or nursery. This is where I belong and, as my father used to say, I will stay here until it falls on my head.

Thank you for the interview.

[1] Malín – a small village close to Kutná Hora, a town in Central Bohemia.

[2] Exchange Program – a year-long youth exchange between families wherein children learn a foreign language and job skills. In Czech this was usually an exchange with German families.

[3] Old Parliament Building – An exquisite work of architecture now known as the Rudolfinum building in Prague.

[4] Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk – the first Czechoslovakian president in office from 1918 to 1935.

[5] Lány – the summer home of Czechoslovak and Czech presidents.

[6] Edward Beneš – the second president after T.G. Masaryk (1935-1938), a president-in-exile (1940-1945), and the President of Czechoslovakia after WW II (1945-1948). Together with T.G. Masaryk and M. R. Štefánik, he took part in the resistance movement during WWI and is one of the founders of Czechoslovakia.

[7] Milan Rastislav Štefánik – a Slovakian politician, Czechoslovakian Minister of War, member of the Czechoslovak National Council and General of the French army. He organized the Czechoslovakian legions during WW I and is seen as one of the founders of Czechoslovakia.

[8] Volunteer Militia – troops of volunteer soldiers that were formed during WW I, mainly in Italy, France, and Russia. They supported Czech and Slovak immigrants in their effort to create an independent Czechoslovakia.

[9] Sudetenland – a region within the Czech territory which held an ethnic-German demographic majority. After the Munich Declaration in 1938, this region was surrendered to Nazi Germany.

[10] Retribution Prisoners - prisoners sentenced on a basis of „retribution decrees" for cooperation and collaboration with Nazi Germany. A state prisoner was also called a political prisoner, as distinguished from those considered actual criminal prisoners.

[11] JUDr. Karel Čížek – a prosecutor who was famous for taking part in communist show-trials during the 1950's.

[12] Pankrác – a prison in Prague.

[13] “Mukl" – a slang term during the Nazi and Communist regimes for "a man on death row" derived from the Czech phrase “muž určený k likvidaci.” In this case, the word referred to any man in prison.

[14] Dagmar Šimková wrote We Were There Too, (Byly jsme tam taky) a memoir about her experiences in prison.

[15] Rudé právo – this Red Right periodical served as the communist party’s daily newspaper up until 1989.

[16] Hana Truncová – nicknamed “Johanka” by her friends, see our interview with this political prisoner also published on this website.

[17] Unified Cooperative Farm (JZD) – this Czechoslovakian farming organization was modeled after the collective farms or agricultural production cooperatives in Soviet Russia. Many farmers were forced to give up their land and machines to the Unified Cooperative Farms.