Julie Hrušková

Julie Hrušková assisted with illegal border crossings in the communist Czechoslovakia. She was accused of espionage and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. She miscarried after a brutal interrogation in Brno. She was released on the amnesty on May 9, 1960.

Interview with Julie Hrušková

"It was meant to be and life just went on. I don't feel any hatred or bitterness." ~Mrs. Julie Hrušková

Interviewer: Klára Pinerová

This interview's English translation has been gratefully edited by Mr. Brian Belensky.

Where did you grow up and what are your early childhood memories?

I was born on May 18, 1928 in Boskovštějn, which is a small village not far from Znojmo (town in southern Moravia). My father worked as a gamekeeper for the Earl of Trautsmandorf. Our house was a gamekeeper's lodge in the middle of nowhere, about thirty minutes from the village where we went to school. I was left-handed and they tried to force me to write with my right hand and they used to slap me on my left. That's why I didn't like school very much. However, we had good teachers. We learned good pensmanship, reading, and even to love literature. I had two sisters and a brother. My brother and I put our cattle out to pasture. My brother liked to go and see the boys in the village. He used to tell me, "Watch the cows now." I always answered, "Okay, but give me something to read," because I used to be an avid reader then. Sometimes I would forget the cows and they would run away. I had quite a nice childhood and I went to my senior school in Jevišovice. It was an hour journey to get there, but the milkmen usually gave me a lift.

Can you remember what your family was doing during the war?

During the war, the property of the Earl came under German custody. There was a person appointed, a Czech, who wanted to appeal to the Germans to open a German grammar school on the castle land. At the time we were already attending senior school when father asked us, "Would you like to go to a German grammar school?" We were being educated along the lines of President Masaryk's philosophy and patriotism, so we said we didn't want to go to that grammar school and our father refused the offer. My father's subordinates were lumberjacks who cut trees and women who planted trees or picked strawberries and raspberries to supply the castle. They eventually said that if Hruška's children weren't going to go to the German grammar school, their children wouldn't go there either. The man who made the initial proposal for the school started to dislike my father, of course. In the end, we moved on to a farm in Blaný and my father worked as a field hand. They grew carrots and other things there. There were hired workers who worked for the Earl and they stole carrots, of course. My father was responsible for that. They brought some carrots to my mother as well and when there was an inspection, they searched the cellars and found some carrots in our cellars too. They all went for a trial and got 10 days in prison. My mother told herself that it could be worse if she appealed, so she accepted the sentence. The hired workers didn't accept the sentence in the end, they appealed, and they got a pardon. So, my mother went to prison in Moravské Budějovice for 10 days during the war and she saw with her own eyes what it was like there. My father was fired, we had to leave the flat, which came with his job. We moved to Černín u Jevišovic and rented a house there. My father was called up to do forced labor in a bakery in Znojmo to replace an Austrian man who had been sent to the battlefront. At that time, Znojmo was an annexed area[1].

My father worked in the bakery until the end of the war. He could have returned to Boskovštějn after the war ended. However during the war, a young gamekeeper with two children started to work there. My father said that he wouldn't like to drive him away. All our relatives, from my mother's side as well as from my father's, were in Znojmo. My sister and I used to smuggle things to them all the time because my mother worked for farmers during the war and used to get food from them. My sister and I would stuff our bras with lard, salami, flour, poppy seed etc., and that's how we smuggled it. Since my relatives had chosen Czech citizenship[2], they got only half-sized food rations and struggled to feed their children. The end of the war saw our family in Černín. We witnessed the Russians going wild there. The Army of Malinovsky marched through and its soldiers raped women all over South Moravia. That's why our parents shut my sister and I in our cellar and we remained there until the end of the war. A doctor told me later that 60 women were raped in the Jevišovice area and seven of them died due to related health problems. One man was shot by the Russians when he was trying to protect his daughters and another man had to watch the rape of his wife. It was atrocious and that's why we disliked the Russians.

What was it like after the war?

They forced the Earl to move away and his castle was converted into a senior citizen's home, but that didn't take place until 1948. In 1945 all of his property was confiscated because he was an Austrian citizen. He resettled and he started a rifle factory in Vienna and sold guns and ammunition there. The Countess left to live with her daughter in Italy and their marriage had probably fallen apart. My father got a job as a gamekeeper in the border area in Vranov nad Dyjí. He got a beautiful hunting ground and a lovely house with lots of bedrooms. My mother didn't want to move there though, because the house was on the side of a hill and to enter the barn and the shed you had to climb steps. The house was below a castle and nearby was a road leading across the border. I finished my senior school during the war and my parents got me a job with a doctor's family where I took care of the doctor's child and cleaned his medical offices. He was a doctor and had a dentist working with him. When the war ended, I wanted to study painting, but my parents didn't agree, so they enrolled me in a so-called "dumpling school," a school for housewives. I only stayed for one year. I had fallen in love with a soldier who was already engaged, so I knew I had to forget him. My sister fell in love with a member of the State secret police[3]. He was a former partisan. To help me forget the soldier, I found a job far away in Aš4, at the western tip of the Republic. My sister and I worked there from September 1946 until 1948. After a falling out with a man in Aš (a town in Western Bohemia), I moved to Brno. There I worked at a lawyer's office. I cared for his two sons and cleaned for him. I read a lot of books there. I also attended a painting course and wanted to study at an art college for a year. Once, a professor who led the painting course came to me to fill out some application papers in order to get me a scholarship for the talented. He asked me, "Are you a member of the Communist Party? Are you a member of the Youth Organization? Oh, you are not. Well, only members are entitled to the scholarship." Later, I had to stop working for the lawyer because it was forbidden to have servants. I found a job in a factory called Matador then and made rubber coats.

How did your anti-state activities start?

Well, 1949 came and there was a boy working in the factory who was in prison in 1948. He did 6 months in prison and wanted to disappear. There was another guy who never said what he was engaged in, but according to what he did mention, I think that it could have been Světlana[4]. Both of them were arrested in 1949 and were questioned for two weeks, but then released, because they wanted to catch more people, I guess. They both decided it was time to disappear. Because they knew how I felt, they came to ask whether I could help them to cross the border. I disliked the fact that they started to imprison foreign soldiers, mainly pilots. I didn't like the communist regime and I opposed it. So I agreed, but told them to take me along. I thought that there would be an army established abroad, like it was during World War II and that I will take part in fighting.

One of those boys, Ruda, had a girlfriend here, who was in the hospital at that time undergoing some treatment and so he had to leave without her. So three of them came to meet me at the lodge. It was in February. I didn't say anything to my parents and I waited until they were gone. We went into the woods and around three o'clock in the afternoon, we were crossing the border. We got stopped by an Austrian financial patrol[5] who knew me because of my father. I didn't know whether they were good guys or bad guys though, so we decided to run away from them. They were good people, however.

How did you get to Vienna and then to the Western Zone?

We continued walking for about twenty kilometers towards the railway and in one small village we persuaded a rail worker to put us up for the night at his railway station. He took me to his office, laid me down on his bed, and went to sleep on the table. He gave us tickets for the Vienna train and also schillings[6] for the tram. We were still in the Russian zone then[7] and had to be very careful. We caught the train at five and at eight in the morning we were already in Vienna. We came to the office of the American CIC[8], and when I reported our arrival there, everybody was surprised, "How come you are here so early? How did you get here so quickly?" They thought we would walk all the way there.

They received a report from the financial patrol that the daughter of gamekeeper Hruška with three young men had crossed the border. Then they subjected us to questioning and put us into a dormitory house. The boys met a Hungarian there who told us that he would take us into the Western Zone provided we pay for his travel. We went to Linz with him where we came to a refugee camp. Soon I went to a dance with another emigrant to get to know what life in freedom was like. Well, I was a young girl then. There I met an American soldier. His name was Frank Ferneti and he soon proposed to me. I was twenty years old then and you only became an adult at the age of 21. So the wedding had to wait. At least, the American managed to get me out of the camp and arranged private accommodation with an Austrian family for me.

Did you know what was going on at home and with your parents?

My parents were very careful at home. I sent a letter from Linz that I had emigrated and told them not to worry about me. They had to report that their daughter left for abroad, but they knew it in three days anyway because they were told by the Austrian financial patrol. An arrest warrant was issued with my name. My mother sent me a secret letter via the financial patrol that said, "Please do not come home. They have issued a warrant for your arrest. If you happen to be in Czechoslovakia, don't go anywhere near the lodge because we are being monitored." There was a soldier guarding the castle and checking all the people going in the direction of the lodge. However, there was another path to the lodge that they didn't know about.

Did you stay in the Austrians' flat all the time or did you visit the camp occasionally to chat with the Czechs?

Well, I was alone among foreigners, so I used to go back to the camp. Czechs lived there that I could have a conversation with. When Frank was on a military maneuver in Germany, I learned during one of my visits to the camp about the possibility participate in espionage activities. They were looking for somebody to secretly go back to Czechoslovakia. I told myself that I would be back from Czechoslovakia well in time for Frank's return from Germany. So together with two other boys, I set off for my country. My mission was to establish an espionage unit in the Republic and bring people, who were in danger of imprisonment, across the border.

What was your motivation for going back to Czechoslovakia despite knowing that you were putting yourself in danger and that you were under arrest?

Most importantly, I wanted to help my people. We stayed in Czechoslovakia for two weeks and each of us had a mission. In two weeks' time we met up again. I was being followed by an agent who worked for the secret police in Brno. His name was Josef Eichler. I didn't have a clue about this at the time. We crossed the border via a different route this time, going through České Budějovice rather than Vranov. However, Eichler learned about our route. We were supposed to take several people across, but in the end they decided not to emigrate due to personal circumstances. That's why we ended up going back as a group four. Ruda, who emigrated with me in February without his fiancée, was taking her with him this time. There was another man returning with us, Franta, who had been involved in espionage since 1948. He was an agent-walker. As we went, he picked up some things at Studánky. I was taking care of his briefcase where he had maps of all border areas from Aš to Šumava, as well as lists of the telephone numbers of all Czech and Slovak factories. We crossed the border in Šumava and went by bus to Linz. Policemen were waiting for us and surrounded the bus with machine guns. Both boys from our group passed through because the police were not looking for them.

They were looking for me and they had my photograph from the agent. They found the suitcase I was carrying and accused me of espionage. They arrested Ruda's fiancée also because she had no identification on her. She knew nothing about what I was doing, so I wasn't afraid that she would reveal me. They handed us both over to the Russians.

What happened next?

At that time, Austria was divided into zones and I was arrested in the Soviet Zone. The Russians offered me cooperation provided that I bring them plans of an American airport. They knew that I was seeing an American soldier in his military quarters and that's why they were very interested in me. However, they wanted to keep Ruda's fiancée as a hostage. I refused because I could have never forgiven myself if I had left her there. I don't like to recollect my experiences from the Russian prison. The interrogations were carried out mostly at night, from about 10 pm until 3 or 4 am. They wouldn't let me sleep during the day. When I laid down on the bench without a mattress or blankets, a soldier who guarded the door of my cell started to kick and bang at the door and I had to get up. Ruda's fiancée caught pneumonia. They called her a doctor and he ordered warmth and more nutritious food. She got mattresses for the bench in her cell, blankets, an electric heater, and officer's meals. I ate almost nothing because all they gave us was borsch and dark bread that even mice refused to eat. Then they handed us over to StB in České Budějovice. Agent Eichler was arrested together with seven Slovaks. Allegedly, he was leading them across the border, but he took them instead straight to the Russians. He was in the same transport to České Budějovice as me, but he requested a transfer to Brno and he was transported there. He managed to "escape" from Brno three times. Eichler crossed the border a couple more times and managed to send many people to prison. He was not present at my trial, but his court records indicate that he had informed against me.

How were you treated in the prison in České Budějovice?

I arrived there in May 1949. I was starving and I ate about two liters of tasty soup and the same amount of spinach with dumplings brought to me by a Moravian prison guard on my arrival. She also reunited me with the girl I had taken across the border. Later, when they called us for questioning at the secret police office in Budějovice, they started to scream at us, but I told them, "You have a reputation in Linz for treating people badly here." The officer in charge then gave an order that they must not touch me and must record everything I said. So, the questionings were okay, without violence. I kept telling them the same thing. I went home to get a good bye blessing from my parents and my case was closed down for two weeks. I was told that I would get about 18 months. Then Brno surprisingly asked for me. In Budějovice, they thought I had some connections there, but I knew that agent Eichler worked in Brno and that it would be much worse there than in Budějovice.

So the questionings continued in Brno?

They wanted to convict us of espionage and they wanted to know more names. I would have to kneel on a chair with my shoes off. When Horák came (one of the StB senior investigators), one of the guards would hit me several times on my feet with a truncheon. When my feet were swollen, I used to wrap a piece of cloth on them and by the morning the pain would have worn off. Sometimes I felt like fainting. The one who was recording me let me sit down when he saw that I was about to faint. Then Horák came, and asked, "Is she speaking? Giving evidence? Naming people? No? Kneel, then!" I wasn't so much afraid of the beating as I was of them giving me an injection to make me speak. That's why I didn't drink water they brought for me from elsewhere.

I refused food and went hungry for several days. Sometimes the girls in the cell gave me a bit of their lunch. There were six to eight of us there. They started to call me "Mosquito" then and people still call me that today. In the cell there was a window, which was above the table and I used to hang onto the window to have a look at the new people they brought in. The jailors started to use that nickname too and it stayed with me until these days.

Were the questionings in Brno much rougher?

There they weren't playing around. I experienced one really rough questioning when they banged my head against a table, dragged me across the room, hammered me against a closet and used whatever they could get hold of. I tried not to fall down. A phone call saved me in the end. They had to get ready for new arrests quickly. A guard took me to Orlí[9], where they put me in solitary confinement. In the early hours of the morning I realized I was bleeding. I was sent to a doctor, but the secret police officers had no time to take me to the hospital like the doctor ordered them to do. I was pregnant with the child of my American soldier. I was in my third month and I miscarried. They left me bleeding there for three days until I was totally drained. Eventually the whole ward of the prison revolted and requested help for me. There was an old jailor who eventually helped me and took responsibility for my transport to the Brno maternity hospital. They saved my life there, but they couldn't save the baby. They treated me really well in the hospital and let me have anything I wanted. The doctors told me that I had to rest. They then changed all the interrogators. I was interrogated by a different man who also recorded everything accurately and the records contained only things that I had already said. Then they handed me over to the custody of the court.

What was the trial like?

I am telling you it was a farce because the verdicts were pre-arranged by the secret police officers anyway. My lawyer wasn't helping me at all because he was a court appointed attorney. I received a sentence of 15 years for espionage. When I was in custody before the trial, I used to write letters to one "mukl"[10] and I found out that we were a part of the same case. He was a driver of the Avia[11] van and he was accused of handing over some documents to Franta, one of the boys I was crossing the border with. That was the reason for them to accuse him of espionage. I spoke to his lawyer and we agreed that I would help him in case he gets mentioned at the trial. During the trial, when he defended himself that he had had no idea of what had been going on, I put my hand up and said that Franta, the agent-walker had boasted to me that he had managed to smuggle some documents on the Avia and logically he couldn't have known anything about it. The judge looked at me and asked me why I didn't say this during the investigation. "Nobody asked me about that. I didn't know this gentleman, so perhaps nobody thought we could have something in common," I answered. The investigators were baffled and in the end he got only three years.

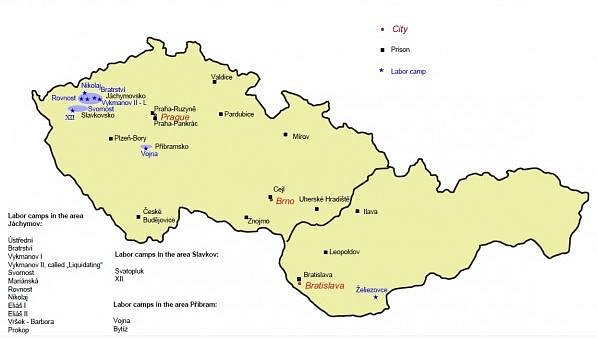

Where did they take you after the trial?

They took me to Znojmo where all inmates were starving and from Znojmo to Charles Square in Prague. From there I went to Kladno[12] where I was seriously considering escaping. Ruda's girlfriend, who had tried to cross the border with us and had been arrested too, was there with me. She didn't want to leave though. I don't know whether it was her or somebody who overheard us by chance who betrayed me, but they called me into their office and told me, "Well, well, so you would like to escape and you are trying to talk the others into going with you." Of course I wanted her to testify and they called her, but she testified against me and therefore they took me to Ruzyně[13]. There was no interrogation and nobody spoke to me about the escape attempt. I was there for about 10 days. They noted "escape" into my papers and put me in transport cell in Pankrác[14] until they transported me to Jičín. I stayed there for four months. In the meantime they sent me to Terezín to work in a prisoners´ work gang. After two weeks they found out that I tried to escape and sent me back to Jičín. From Jičín they transported us to Lomnice nad Popelkou. A women prisoner, who was a climber, had escaped from there shortly before we arrived. She had escaped through a bathroom window on the second floor and people said she had managed to get across the border and abroad. We weaved canvas in Lomnice. We stayed there for about four months again and then were transported to Hostinné, where they had a spinning factory. We worked at the wet hall and swapped shifts with civilian workers. The work was hard, but we had a good commander. He allowed us to take parcels from visitors and we also took money on the sly. The commander went shopping in town every day together with a retribution prisoner[15] and she bought everything for us. From there we were transported to Hradec Králové. It was 1952 when they transported me to Pardubice where I stayed there until my release.

What was your arrival at Pardubice[16] like?

Prisoners were transported from Litoměřice, Česká Lípa, and Chrudim. We were taken from Hostinné to Hradec Králové and then to Pardubice. There we noticed that something peculiar was going on because the guards treated us nicely and were telling us, "Girls, this isn't going to be a pleasant experience for you." We were actually the second transport to arrive at Pardubice. The first one was from Pankrác. We were used to a certain look of the jailors' shoulder boards (epaulettes) and all of a sudden we saw red shoulder boards and we immediately knew we were being guarded by the secret police[17]. They gathered us on the prison yard where they gave us numbers. I got number 176. We were put into one cell, which was a big hall divided into double rooms. We lived on the first floor because there were offices on the ground floor. It was called "A" section because there were also men in the "B" section. Then they gathered us in front of the "A" section, brought straw and we had to stuff our mattresses. We were given covers and mess tins. We had to hand in our civilian clothes and got prison clothes. We had no work place yet, because part of the prison was still being built. So in the beginning our job was to help the men with carrying bricks. We also scrubbed floors, which were pitch black. There was a madman of a captain and he used to come in wearing boots covered in mud and he used to say, "Now, scrub it all again!" We used glass, straw, and cold water for scrubbing the floors. There were about 80 of us at the beginning. When we had free time, we used to go lie down and chat behind the main square where there was grass and apple trees and also some vegetables growing. That lasted about a month. At first, they called for somebody to work in the garden, but I didn't want to do that. I first worked in the cable room, then in the sewing room, and then the cutting room.

In September 1955 there was a hunger strike in Pardubice. What was your experience with it?

That was when I was working in the sewing room and the hunger strike originally started at the knitting room. We didn't know who started it and why. It was only later that we learnt that the overseer at the knitting room was a downright sadist, but we never had to deal with her. They rushed us to the yard and we were surrounded by secret police officers with machine guns and a ministerial commission came for inspection. The girls who started the whole thing were taken to a secret police office in Pardubice. At that time, there was a change in leadership, (warden) Sultán was replaced by (warden) Huňáček. When some of the women were taken to the secret police office, Merina , my closest friend in prison, and I told ourselves that we would start a hunger strike to protest. We were put into a run-down building, which started to fall down after the "big move" in the summer of 1955. The hunger strikers were divided into groups of about three and put into cells. The girls who started the hunger strike came back from the Pardubice secret police office. Most of the women had finished their hunger strike, but I decided to go on. There were three of us in our cell. Seven days had already passed and they made a decision to feed us. Božka Tomášková went first, but when she learnt that the others had finished the hunger strike, she stopped it too. Then Vendula Švecová went and she tried to fight, but they fed her anyway in the end. I was the last. When they started to hold me tight, I told them, "Look it's beneath my dignity to fight with you. You have an order to feed me, so feed me." So they put in the feeding tube, poured in the broth. When they were pulling it out, I threw up all over Ruzyňák, a jailor who was very meticulous about his uniform. They took me to a cell next to Vendula's. All in all, we were on hunger strike fortwo weeks and we used the Morse code to communicate. Vendula messaged me that she was unwell. I remember they told us that they would be taking us to the hospital in Pardubice the following day to feed us through the nose not mouth. I was looking forward to it because I thought I would shout out what was going on in front of the doctors. Vendula kept messaging that she was feeling sick. So I messaged her back to start eating and that I was feeling well so far and would go to hospital on my own. However, she collapsed in the evening and wouldn't start eating without me. So I had to end my hunger strike.

What was the situation with hygiene in the prison? What about washing clothes or having a bath for example?

There was filth in Kladno, so we did our washing by soaking our clothes in cold water, soaping it, rolling it, and rinsing it off the next day. The most important for us was to be clean during the visiting times. We did the ironing mattress style. We slept on the clothes and in the morning we ironed out the creases in the skirts and blouses. We could only use cold water. If there was some warm water we were happy to be able to use it for bathing. In Pardubice we went to a washroom once a week or once in a fortnight, but I never went because it all depended on which jailor was on duty. Some of them were bitches and let us soap ourselves and then shouted to finish up and either turned off the water or turned on the cold. Later on I found out that the jailors came there to watch us. So I didn't want to show off. During the whole time in prison, I was in the washroom only about two times.

What was your experience with guards, both male and female?

In the sewing room, the overseer was Permoník and he was good. For example he saw me with the nun and he said, "Hrušková, you have been talking to Huberta for the last thirty minutes!" "I am only explaining the sewing to her, because she can't get her head around it." He never reported on anyone. Anka Suchá was the one who worked us the most. Then there was another one, whom we nicknamed "stepped margarine" and she used to be a prostitute. There was also Jáno Škrhola. He was always pushing me to do part time jobs. Then there was a guy who came from close to where I live now. We used to call him Prince Bayaya (Czech fairy tale character). Once the guards tossed cells and I forgot to hide my English textbook. I gave up on seeing it again. In a couple of days Bayaya came and told me, "I dumped your English behind the closet," and it was really there! I never told anyone about it though.

Could you do anything in your free time?

There was an art club and later on Taussigová-Potůčková[18] became its organizer. She was a communist and I stopped going there because I couldn't stand it. I had my principles. She was put in my cell at one stage. It was during the events in Hungary that she was worried that we would hurt her. She was very lonely in the prison and I have to say that she had a bad time there. In the "C" section I got to know Nina Svobodová[19], a writer who wrote poems which I used to know them by heart. She had the idea to do theater there. After we finished work, we used to put on short plays. I used to paint the masks and the faces of the girls who acted and did anything else that needed to be done. We also used to entertain ourselves by listening to the news on the prison radio every day at 7 pm. I used to write down the most important news, make notes and comments, and when the afternoon shift came back from work at 10 pm, I used to read it for them. Sometimes we could even listen to classical music on the prison radio. However, the prison radio was on only during the last couple of years of my stay. It was the same with newspapers and we used to have one newspaper for the whole building. I remember once we organized a ball. We used to play music in the bathroom. One girl would whistle on the comb, another would sing, I would play the drum, and the rest of the girls would dance. Nina Svobodová saw it and liked it very much. This was still in the winter of 1953. Nina liked it so much that she wrote a program and the girls dressed up in masks and played historical parts and characters from fairy tales. There were seven dwarves, Admiral Nelson, a princess with a star on her brow, a Hawaiian dancer, the Roman emperor Hadrian, and others that I cannot recollect. The musicians were supposed to be beetles. We made antennas, but mine kept falling off my head because I had shaved my hair off the previous autumn, so I couldn‘t be bothered and took them off. In the end the people in masks were sent to solitary confinement and since I had no mask, I wasn't sent to solitary. People said that the chief commander of the prison really regretted not having seen our performance. His deputy, whom we called Pepánek, came. The girls spent about two weeks in solitary. A couple of days earlier, Jiřina Štěpničková[20] came and she was completely taken aback with all this, especially with our masks.

Did you ever receive or send a moták (secret message)[21] during your imprisonment?

Of course, I sent many of them in prison. In every prison I used to send secret messages to somebody, mostly to men. My mom used to send me secret messages too. She would put them into scones because they didn't check them. They only cut big marble cakes. I used to tell people I trusted to eat carefully because there might be a secret message inside. I always had to wait until the message was found and only then would I hand out the scones. I also used to carry secret messages during visits in Pardubice. I would glue one to my palm and when I stretched out my hand to give a handshake, I would squeeze the person's hand. My mother knew that I had something in there, so she took the message and pretended to cry and wipe her tears and that's how she put the message in her pocket. In 1958 we were allowed to sit at a table. Before then we always received visitors behind railings. I would like to share a little story with you. In 1956, the women from the "Castle,"[22] which was a closed department, wrote letters to the UN Secretary Hammarskjöld.[23] In 1958 when they transported them back from Prague, where they were serving their punishment, Zenáhlíková, Dáša Šimková,[24] and Irenka Vlachová again wrote similar letters to Hammarskjöld and I joined in. I handed these letters in the form of a secret message to my mother. At that time, my parents didn't live close to the border, but they lived in Věstonice[25] and had no way of smuggling the letters abroad . My mother was afraid and that's why she sewed them into the insides of an armchair. When I came back from prison, I had long forgotten about it and my mother didn't mention it either. In 2006 I wanted to throw the armchair away, but had this hunch and decided to cut the armchair open. A tinfoil packet fell out and there they were the letters from 1958! Another thing I should mention is that I also exchanged secret messages with Merina, who was my best friend in prison. I can't remember anymore why, but she got a placement at the "Castle." She was scrupulous and was very honest with everybody. The commander, whom we nicknamed Sultán, knew about our secret messaging, but he had no idea how we exchanged the messages. I was working in the cutting room, where the pay was a bit better and we were also allowed to receive parcels once every six weeks or two months. Once, at Christmas, I got a parcel and the commander brought it to me. Sultán was the commander then. He came to the "Castle" the following day and saw that Merina had the sweets from my parcel spread on her bed cover. Sultán told her, "Jandová, I am not going to punish neither you nor Hrušková, but tell me how you managed to get that here?" He was constantly trying to figure out how I was sneaking the things there. Well, what I did was when I went to the toilet at night, I crawled through the railings there. Merina and I had an agreement about the time I would go through and she would wait for a signal and then cast down a thread with her bundle of secret messages, or I would tie my bundle onto the thread and she would pull it up to the second floor where the "Castle" was.

In prison, did you know about women who decided to cooperate and give information about other prisoners?

One never knew who could be coerced into cooperation. They used promises with some and threats to take away children and put them into foster homes with others. It was obvious that any mother would do anything to save her family. They never tried to persuade me because they knew that I had had a big chance with the Russians, who had tried to persuade me into cooperation, but I had refused. I remember one woman who agreed up to cooperate. This was during the time of Huňáček in 1958. There was a search raid and they found my English textbook. I had studied English the day before and had pulled out a box with a double bottom where my English textbook was hidden. One of the inmates asked me, "Mosquito, how was it discovered?" I replied, "All right (in English)," while staring into the box. I recalled that Věra was there that day. Her husband was imprisoned, her father was abroad and she came from a -well-to-do family in the region of Hradec. They threatened to put her child into a children's home. I wanted to verify it first. Once, when we were sitting in our cell alone, I started to write a secret message for one of the male prisoners. She came to me and asked, "Mosquito, what are you writing?" "Oh, I am just writing to one of the boys, to one of the ‘mukls'." It was a trap I set for her. In a couple of days, I was called in for questioning, "You are corresponding with the male prisoners!" and the guard started to recite the first line of my message. So I told him, "How can you know that? Have you found it? That's interesting!" I didn't send the message. I burnt it instead, but I played stupid. "Did you find him? Did you punish him?" The interrogator responded, "Of course he got a punishment and you will get one too." I then said, "What for? You know, I never sent any message to anybody. I just wanted proof and you will see the consequences in a little while." The following day I wrote a letter to the Ministry of Interior saying that they made people spy on each other and threaten to put prisoners' children into foster homes. All in all, it was mainly a complaint to the Ministry about the conditions. I said that they bossed us around, they put us into the "Dump" (solitary confinement, wet concrete cell) for nothing, gave us food only every two days, that it was freezing there, and we had to sleep on the cement floor etc. I gave it to Škrhola and asked him to hand it over to the commander and said that I was going to start a hunger strike. They brought me to the secret police office in Pardubice where a doctor came to check on me every day. On the seventh day she told me, "If I can give you a piece of advice, the letter has been delivered to the Ministry. They will come to carry out an investigation, but you are risking your health with the hunger strike." So, in the end, I stopped my hunger strike and they put me back into the very same cell. I learned that the commander had come to the cell to do a prisoner count one evening and he said, "Věra, Hrušková is spreading the news that you are an informer." She went red. I didn't tell anybody, but he told her in public in front of the whole cell because they didn't need her anymore. I came back to the cell and she wouldn't speak to me. I was thinking, "You signed because you were cornered, so I can't condemn you, but I wanted to help you. I hadn't done it to get revenge. That's why I wrote the letter to the Ministry." About a month later, the Ministry people came to carry out an investigation, so I explained the situation to them and the prison was probably reprimanded for letting us sleep on the cement floor, because from then on there were always mattresses. Christmas time came and I went around the cell to give holiday greetings to everyone. We always used to put on a show at Christmas, because we didn't want all the mothers to be sad that they are alone and separated from their children. So we used to organize a Christmas pageant. Every year I made a nativity scene out of paper and every year it got confiscated. So I came to Věra and told her, "Věruška, I didn't want to hurt you, I wanted to help you." She held me like this and said, "Mosquito, thanks a lot because now they are letting me be."

You have mentioned guards tossing cells, what was that like?

They usually tossed the cells when we were at work. Sometimes it was really thorough. They ripped straw from mattresses and threw it with jam and sugar all together into one big heap. Once I was ill and they came to do a search raid. The trouble was that I was hiding things for the girls in my cell in my bed. The guard Ruzyňák came. He was a scary man. He demanded, "How come you are in bed? We came to toss cells." I replied, "I am ill. Do I have to get up?" I didn't want to leave my bed because I had all those things that needed to be protected like photos, sweaters and other things under my duvet. So he told me, "You can stay in bed then. We'll be decent." So I covered my head because I didn't want to watch it and they were done in a minute.

I heard that there was a "big move" in 1955 in Pardubice. Can you describe what it was like?

Once, they told us that we were going to move. Everybody from the "A" section had to move to the "B" section and vice versa. That was during the times of Sultán, when he started seeing Jana, a doctor, in her office. We were also told that we needed to move the closets. In fact, the whole prison was being moved around. We were moving down from the third floor and were dragging the closets down the steps. The whole building was shaking. All of a sudden somebody found out that there was a hole in the third floor and it was getting bigger. They reported it and that was the end of the "big move." They brought in building inspectors from the Ministry, which came the following day and they told us to sleep wherever we could find space and that nobody was allowed to enter the third floor. So everybody found a sleeping place with people they knew. Eventually, they found out that the third floor needed to be demolished because of disrupted building structure. Later, they put us into a stable that used to be a storage room for textiles and moved all the textiles from there to barracks in Pardubice. In the stable, Vlasta Nováčková found a nest of newborn mice in the pocket of her jacket. Mice crawled into all our clothes, so we started to hang them up on hooks on the walls.

You met various types of people in prison. Could you say something about them?

For example we lived together with retribution prisoners and they used to say, "If it was up to us, we would pave Wenceslas Square with your heads." They hated us. What's more there were guards from concentration camps and they met with their former prisoners there. The retribution prisoners were sent to Germany in 1955. After 1955, there were only us, the political prisoners in Pardubice, and then later on criminal prisoners, who started to come in gradually. The murderers used to say, "We only killed one person, but you wanted to kill the whole nation." In short, some were with us and some against us. The prostitutes from Ostrava were the worst. They spoke coarsely about this or that in a way that would make your stomach turn. They came in the final years of my internment, towards the end of the fifties. Then there were prisoners who had defrauded others of money. Some of them were innocent, but others were just crooks. Gypsies lived there too. Guards never intervened when they fought among themselves. However, the gypsies were never aggressive to us.

It seems that you always knew how to take care of yourself in prison and you had no problems speaking out. Except for the hunger strike in 1955, in which you were the last person to stop, were there some other forms of protests?

I have a funny story from Kladno prison. We refused to move because of a fart. There were about 32 women in our cell and our woman commander lived right next to us. It was the only building without bedbugs. The retribution prisoners lived opposite to our building. The commander used to invite her lover over and one of my inmates used to watch them through the cracks in the cabin's wood walls. Once, the lover let out a fart while having sex. The inmate who was watching them got carried away and shouted out loud, "Girls, he farted while doing it!" Of course, the commander heard it. She went home for the weekend. Another commander came and because I was the cell leader at that time, he told me, "Hrušková, this is a list according to which this cell is going to be divided and moved into different cells. This room is going to be vacated and the commander will use it as a storage room." I replied, "Commander, wait a second, we are not going to move because of a fart, are we?" He gave me a slap in my face and I thanked him for it. He turned and left. He was followed by another commander and he gave me a punch in the face. My nose started to bleed, so I left for the washroom to try and stop the bleeding. He then proceeded to beat up all prisoners from the cell. My nose was broken. In 1962, I had a tumor close to my nose and when I was having it removed by a plastic surgeon, the doctors tried to fix my nose bones but they couldn't do it. The bones healed up badly and the wound was too old. I suffered from frequent nose bleeding then, especially in hot weather. I still suffer from it today, especially when I am ill with cold.

To get back to the revolt, we refused to move then and the following Monday a truck came and all of us were transported to Karlák[26]. We were put into a large sitting room and one by one were questioned. I, being the cell leader, went first. I told them the truth. When the fifth inmate came, the interrogators were already protesting, "We don't want to hear about the fart again!" The investigation was soon dropped. We crossed our fingers, got some paper from somewhere and played cards. After two weeks we were transported back to Kladno. I knew they were going to move us. The commander was not allowed to bring her lover there anymore. We were moved into a building with bedbugs. The bedbugs liked my blood very much and they were killing me.

What was your release like?

When the amnesty came, they read the decree out to us. We didn't laugh. We weren't happy at all. Everybody was wondering why? There had been a rumor going about for some time, because they moved lots of people from the "C" and "D" section to the "B" section in March. In section "C" they only left one room with nuns and then murderers and prostitutes came. They emptied a room in section "A" for us and we were trying to find out why they had put us together. In the end, we found out that allegedly we were all sentenced for espionage against the Russians. So, I was thinking that the amnesty wouldn't probably apply to us. Each of us had to have an agreement from their hometown or village saying that they would be accepted back. My brother-in-law, my younger sister's husband, was a communist. I would say he was an idealist though, and he trusted the communists. He was chairman of the village council here in Věstonice and hence he knew when my release would be scheduled. My mother told me that on the day of my release, he came to our place a couple of times to ask whether I had already arrived. They took us to the train station in small groups, one group at a time, because they were probably afraid that we would start a revolution there. Our tickets had been bought in advance and they escorted me to the train and off I went straight away. We traveled in our prison uniforms. I came to Brno, but I went to see a friend from the prison first and then went home after that. I rang the doorbell, my mother came to answer the door and asked me, "Are you just visiting or is this permanent?" I said, "It looks like I have been released, but I'll have probation for 10 years." Then my mother went on to tell me that we would go and visit all our relatives and we would see where we could get a warm welcome. In the end, everybody was glad that I was back, so there was a happy ending to it.

You were sentenced at the age of twenty and spent eleven years of your youth in prison. What was the most important thing that kept you so strong?

Faith. I was friends with a girl who was imprisoned because of her Catholic activities. We used to go for walks together and she taught me the whole mass by heart. That way we were able to hold masses in the prison yard. My friend was even able to sneak in some wafers. We were constantly being persecuted because of these "masses." Nuns used to do it in a similar way. The jailors found out and we were sent to isolation cells. However, during my prison years I kept my faith and I still keep it today. I always say that the mills of God have a nuclear power engine. I grew up in a religious family and I saw it all as my punishment. My mother warned me not to come back to the Republic, but I wouldn't listen. I also promised the American I wouldn't go back to Czechoslovakia and I betrayed him. My mother sent me a letter in Linz saying that there had been a warrant of arrest issued in my name and urging me not to come back and avoid our forest lodge. I didn't listen. As I am saying, it was God's punishment for my imprudence and disobedience. Still, I managed to come to terms with it. I still kept my faith.

Apart from the problems with your nose cartilage, do you suffer from any other health conditions as a result of your stay in prison and cruelties during interrogations?

As a result of my miscarriage and long imprisonment, I developed a uterine tumour at the age of 45. First, it had been only the size of a nut, but in three months it grew into the size of a baby's head. I had to undergo a serious operation during which my uterus and one of my ovaries were removed and the other sterilized. That ended my hopes of getting pregnant. This was the biggest blow I suffered from the Bolshevik regime.

Did you have a chance to meet your American boyfriend later on?

No, I did not. I wrote him a letter from prison, but they didn't send it to him to America. Later, when I was released during the mass amnesty in 1960, I didn't know how to contact him. I was being watched and on the top of it, I was on a conditional discharge with ten years probation. So, I bought a book called "Travels through Czechoslovakia" and sent it to him. There was a photo of Věstonice inside on which I wrote in English, "This is my home." In three months time the book came back though. A few years ago, I eventually managed to track him down.

The children of a relative of mine with good computer skills, found him using his name and date of birth. They found out that he died in 1991, just after the Revolution. Computers were not common in 1989, so there was no way for me to find him. That's why I only found him after his death.

Is it at all possible to get over all the suffering, pain, and loss that you have been through?

When I was in prison I always had strong support from my parents. Nevertheless, I had to come to terms with the fact that I lost my child. I always say that it was meant to be and life just went on. I have managed to reconcile with everything. I don't feel any hatred or bitterness. When I came back from prison at the age of thirty-two, I wanted to have a baby, but I couldn't anymore. It just wasn't possible after eleven years in prison. So, I stayed alone, faithful to my American.

Thank you very much for the interview.

[1] Annexed to the area of the Third Reich.

[2] Choosing citizenship - After signing the Munich Treaty in September 1938, according to which Czechoslovakia surrendered a part of its border regions (Sudetenland amongst others) to Germany, the Czechs who stayed in the Sudetenland, as well as those who moved away, were asked to state whether they wanted Czech or German nationality. However, those who claimed Czech nationality lost the right to live at their original address and those who chose German nationality were in danger of being drafted into the Wehrmacht.

[3] State secret police known under the abbreviation StB, was a political police force in Czechoslovakia during the communist era.

[4] Světlana was a resistance group in Czechoslovakia, which was founded by a former partisan chief Josef Vávra-Stařík. It was founded in 1948 in the city of Zlín which was at that time re-named to Gottwaldov as a tribute to President Gottwald. The group was named after Světlana Vávra-Stařík, the daughter of Vávra-Stařík. The group had three main leaders: Vávra-Stařík, Josef Matouš and Rudolf Lenhard. From March 1949 until May 1950, StB arrested 400 citizens at the border of the Moravian and Silesian region and also in South and Central Moravia. The prosecutors, together with StB officers, put the members of Světlana into 16 groups, which were sentenced in 16 trials during two years, starting in April 1950. Eleven people were sentenced to death and executed, including Vávra-Stařík, Matouš, and Lenhard.

[5] Financial patrol monitored whether state and financial borders were respected.

[6] Schillings. Austrian currency used at that time.

[7] After the war, Austria was divided into four occupation zones as Germany was. This division lasted until 1955.

[8] Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) was an American intelligence service established during WWII in December 1943. Its task was to search for and eliminate German agents in the ranks of allied armies. After WWII its activities were focused on the Soviet Bloc, and especially in the 50's it recruited and trained agents who were employed to work within the region of Soviet influence including Czechoslovakia.

[9] Orlí - a prison in Brno.

[10] "Mukl" comes from the Czech abbreviation of - "a man on death row" (in Czech: muž určený k likvidaci). It was a label given to political prisoners imprisoned by communist or Nazi regimes who were not supposed to be released and were supposed to die in prisons or concentration camps. Later on, this label started to be used for all political prisoners.

[11] Avia - a lorry.

[12] Kladno - a town in Central Bohemia.

[13] Ruzyně - a prison in Prague.

[14] Pankrác - a prison in Prague.

[15] Retribution prisoners – prisoners sentenced on the basis of „retribution decrees" for cooperation and collaboration with Nazi Germany. "Political" prisoners were classified as identical to "state" prisoners, although there was a separate category for criminals.

[16] Pardubice - there was a prison for women. The first transport of political female prisoners arrived on March 26, 1952 and was supposed to prepare the location for coming prisoners. Mostly political prisoners with high sentences were placed into this prison.

[17] On May 1, 1951, the Ministry of Justice handed the Pardubice prison to the Home Office. From then on, the security ceased to be provided by prison guards and was taken care of by the police. Prisoners agreed that as soon as the institution was handed over to the Home Office, the prison conditions tightened up, violence occurred on a larger scale and stricter disciplinary rules were introduced.

[18] Jarmila Taussigová-Potůčková (1914-) - a member of the Communist Party, one of the leading members of the Party Inspection Committee. She was responsible for political and stalwart activities within the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. She was sentenced in a trumped-up trial with Rudolf Slánský in 1952 and released in the amnesty in 1960.

[19] Nina Svobodová (1902 - 1988) - a Czech writer and journalist engaged in the activities of Catholic cultural movement, worked as an editor for the calendar "Czechoslovak Woman" and cooperated with the weekly "Catholic Woman." Member of the People's Party and sentenced in the Liberec show trial.

[20] Jiřina Štěpničková (1912 - 1985) - a Czechoslovak theater and film actress. She was sentenced to 15 years in prison in a trial in 1952.

[21] "moták" - a secret message usually distributed among prisoners on a small piece of paper.

[22] Special prison department called the ‘Castle' for prominent politically engaged women. For example Růžena Vacková,a professor at Charles University, Dagmar Skálová, and Vlasta Charvátová were imprisoned there. Altogether there were 64 female prisoners. In addition there was a department established for nuns, which was called the "Vatican," as well as another department called "Underworld" where women with sexually transmitted diseases, prostitutes, women with mental disorders, and recidivists were placed.

[23] On the eve of June 29, 1956, 12 prisoners in the "Castle" department wrote letters to the UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld which described reasons and means of arrest procedures, together with the conditions in Czechoslovakian prisons, and work camps. The women were demanding their rights as political prisoners. The letters were supplemented with translations according to the language skills of each individual author. Naturally, the letters were never sent out and were enclosed into the personal prison files of their authors.

[24] Dagmar Šimková wrote a book of her prison memories called "Byly jsme tam taky" (We Were There Too).

[25] Věstonice - a village in Southern Moravia.

[26] Prison at Charles Square in Prague.