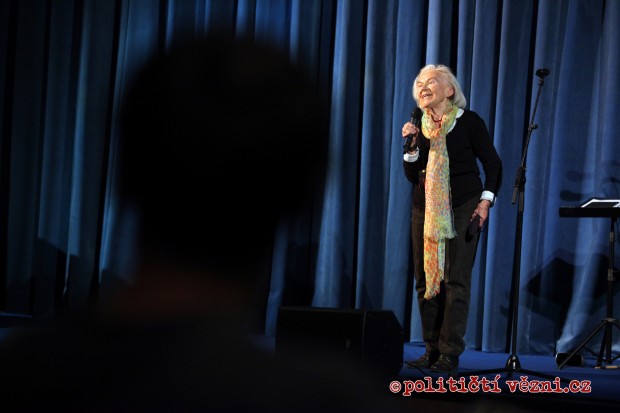

Hana Truncová

Interview with Mrs. Hana Truncová

"It gave me confidence and from the political view it gave me the anti-communist view." ~Mrs. Hana Truncová

Interviewer: Klára Pinerová

This interview's English translation has been gratefully edited by Ms.Olivia Webb.

Can you tell us about your parents, childhood and youth?

Of course, with pleasure. I was born in Teplice[1] in a trade family. My father's ancestors came from the area of the Křivoklát forests and they moved to the border area sometime in the 19th century. I have a sister, and I must say that we had a very nice childhood. We had a big garden and many friends. All of my friends came from a Czech, German or Jewish environment. The town of Teplice had the same structure – one-third was Czech, one-third German and one-third Jewish. You can see the evidence of this in Teplice cemeteries. During the First Republic I lived in a border area. We also stayed there during the war. We were lucky to have a little shortwave radio at home. At 10 pm I used to listen to the Calling from London[2] with my father. It was very risky because we lived in a terraced house – and since the radio stood by the wall, my father had to be careful to isolate the sound so that none of our neighbours would know that we were listening to that radio program. It could have cost us our lives.

Did you witness the post-war transfer[3]?

Yes, in those days they drove families out of their houses. The fathers were not usually at home, so mothers and children were just rooted out basically from their kitchens. That was the beginning of the transfer in June 1945. Those people were not even allowed to take 30 kilograms of their personal belongings (which was allowed later on), they just had to go. They were kicked out from their homes. Partly I am not so surprised; it was a kind of revenge. People were excited and did not think reasonably or humanely. Human relationships were gradually disappearing. I lost many friends from school due to the transfer. Also my family lost many good friends who had nothing to do with Hitler. I used to know some Czech families who returned to the border area after 1945, but they could not live there so they went back inland.

The Czech-German border areas got resettled during the post-war period. Most of the houses, farms, flats, land, factories, valuables and accounts suddenly did not belong to anybody and were being given away. People who went there and were able to tolerate owning someone else's property got it.

How did you spend February 1948[4]?

I had a part-time job in one building company in Teplice from June 1945 to February. It was a part-time job because I also helped my father with administration in his business. We had quite a big joiner's workshop and lived in a busy street. Hundreds of people used to walk past our house on their way to work. It was in February 1948 when my mom opened the window at 10 am and was very surprised to see many people walking home from work. I stayed at work at that time. I worked in a building company and my office was on the ground floor. There were about 25 employees in the company and many of them would stand on their tiptoes by the window to see whether I was sitting at my table. I think one of them wagged his finger at me. My boss helped me to stay there and keep on working, but unfortunately it was my sister who was dismissed from work. She used to work in a tent and canvas factory. That sacking prompted her to apply for legal emigration from Czechoslovakia.

She worked as an organist in a parish church in Novosedlice. The head of the parish was Dr. Johan Thies, an Austrian who was not driven out but a man who wanted to move to Austria. Thanks to him my sister had contacts for all the offices in Prague and she did the same thing as him. She applied for emigration and she did not accept the Czechoslovak citizenship which was recently given to people during communism. She was given permission to emigrate in autumn 1950. The permission was valid until the end of March 1951. She moved to Austria, to the Russian zone, where she got help from our father's business partner. He lent her an identification card of another woman who looked a bit like my sister. Using that ID card she got to the western zone and later to Western Germany where she stayed.

Did you have any problems due to your sister's emigration?

The problems started after I was arrested. The Czechoslovak State Security would threaten me during the questioning by saying, "Your sister is in Austria in the Russian zone and we will bring her here." At that time I did not know if she managed to escape from there or not. I was very scared because they were able to arrest anyone they wanted, put him in a car and drive him back to Czechoslovakia. It would not have been the first or the last case, and it was very easy for them to arrest people in the Russian zone.

As you have already mentioned being arrested and questioned, I would like to ask, why did they arrest you? What subversive activities did you do?

I longed for freedom, you know. I was a child from the border area and I remember that, during skiing in the Krušné Mountains we could easily cross the borders. The custom officer only asked, "How long will you stay there, kids? Where will you go? Come back afterwards." I was used to a life full of freedom in the borders. When I saw all those changes after the war – no tourism, no opportunities, no culture, no books, magazines or newspapers – I hated it. It was all very chauvinistic and I did not like it. I longed for living in a different political system, and that is why I was brave enough to do something against that. We had contacts for the people on the border crossings; there was one man who took people from Eastern Germany, from Zinwald and from Czechoslovak Cínovec. I did that for quite a lot of money, because he also had to make his living. I used to send him some people who had to escape from the country; for example they had to run away from the threat of being arrested. So suddenly my family and I became part of the group who helped people cross the borders. I do not know if one of those people we helped was a police informer, but I think we must have been under observation because soon we realized that something had started happening around us.

So you were arrested for illegally taking people across the borders?

Apart from helping people cross the borders, we also printed leaflets. There were no computers in those days, so we wrote the leaflets on good quality typewriters where we could make more copies. Sometimes we printed ten copies at once. The leaflets were then distributed in different ways. At that time I had my part-time job and a really nice boss. He did not have a clue about my plans and activities. He used to take us for trips; we distributed our leaflets there and he never found out.

We also put the leaflets in peoples' letterboxes. The net had already started closing in on us. Then I started to work in a Spa in Teplice and had a great boss again – Mr Sova. I wrote a diary in German stenography in those times. Yet, I could feel it with my sixth sense that the problems were coming. I brought my diaries to work and put them in an old folder. We used to go for lunch with spa guests in the canteen. One day my boss came in and told me not to come back to work anymore. The State Security was already in the office, looking through my bag, typewriter, and everything else that was accessible. Luckily they did not check the old folders. I knew I had to do something with the diaries and could not take them back home. I had one single colleague, his name was Emil Topinka, and I asked him to save those diaries for me. He took them and hid them for a long time. When we were nearly sentenced he dared to bring them to my future husband's mother, Mrs Marie Truncová. She was scared to have those at home, so she buried them somewhere in the shed.

Did you find them in the end?

Yes, I did, but I must tell you I am completely lost with them today. For example the names are not written in stenography and I do not remember them or cannot even imagine most of those people today.

How did your arrest happen?

I was arrested in my office in the Imperial Spa. The Emperor used to stay there during the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. That day I could see a black Tatraplan [type of] car coming – I was born at 11 o'clock and arrested at the same time. They did the house search and took me to Ústí nad Labem (Aussig). My mother experienced many more house searches after my father was arrested. Male prison officers were not allowed to examine me, so a female one came to do it. When I saw her I could not believe my eyes, and she felt the same, because we knew each other by sight. She used to work for that building company where I had my part time job. She joined State Security after that and then she was there to examine me. She let me keep a gold chain and a little gold crucifix. She had to take the other things I had. I did not see my earrings, valuable rings or watch again. It had to go. And the chain with the crucifix had to go soon as well. We had to wear male shirts with no collars so our necks were uncovered. I took it off in my solitary cell, but there was nowhere to put it. There was no chance. The officers always checked the only pocket you had and your hands. I would have had to swallow it.

What did the cells in Ústí nad Labem look like?

They were little cells under the pavement with no ventilation. Only when a prison officer opened the door, you could smell the mustiness from the corridor. Everything was underground, you got down there by an elevator and there were prison bars everywhere. There were only solitary cells in Ústí nad Labem – no hygiene, no showers, and no hot or cold water in the cell. There was a so called French toilet embedded in the floor, but no water. There was not even a jug, so you had nothing to drink. The air was dry, so dry and not fresh. The cell was about three by three steps big and there was a big wooden bunk-bed which could not be folded and was full of bedbugs. I wasn't allowed to lay down on the bed during the day, only at night. There were no blankets, so you had to lie on the bed with hands next to your body and the bedbugs came out of the bed. That was horrible. The prison officer opened the door to the corridor in the morning and we took turns to have our morning hygiene. There was no toothbrush and I did not comb my hair for about three months. There was one basin with cold water in the corridor and only one towel hanging next to it. You could see blood stains of all the prisoners on the towel. I am very sensitive when it comes to hygiene, but I must admit that at that time I did not mind the dirty towel, because I knew that some of my close friends or relatives used it as well.

Did you know about any of your close friends or relatives, for example your father or future husband, being in prison too?

My fiancé was arrested before me and I used to bring him clean clothes before my arrest, so I knew about him. I found out that some other people were there as well because I heard some people whistling. We all liked and used to use one tune by Beethoven, and I could hear that tune in the prison, so I knew there had to be someone from our group. After years I found out, that my future husband engraved some message for me on an aluminum dish because he thought that the dishes went around the prison and I might have been given food in that one. Yet, I was a naive prisoner and did not search for secret messages. The prison officers realized that he was doing that and he had to clean all the dishes. After that, the regime of tin spoons and tin dishes started and lasted for many years. It was a big punishment for me, even bigger than correction, because we were given neither a knife to cut our food nor fork. There was only that spoon and the dish. For years we washed the dishes in cold water because there wasn't any hot water in the prison. For some time we had our own dish, but then it changed and we had to take them to the kitchen and pick them up from there as well.

Did any prison officer help you?

It was in the prison in Litoměřice where they sometimes took me when I didn't give evidence to the State Security. One officer there helped me. It was an older man who probably also worked there before the war. That generation was later swapped for newly educated staff. Although I did not know that something like a hunger-strike existed in prisons, I stopped eating. Over the course of time I think they might have put something into my food. I was so mentally and physically exhausted that I started to be able to perceive everything through my nose. I used smell more than sight. There was a tip-up table in the cell, which I was allowed to use only when they gave me that bit of food. I could smell some disgusting odour rather than a beautiful smell of wood from that table. So I stopped eating. That old prison officer noticed that and even though he was not supposed to, he came to my cell and told me to eat and not to lose energy. I do not remember if I asked him or if it was he who noticed, but he brought me a comb. It was a dirty comb from some other prisoner, but it did not matter, I cleaned it.

How did the examiners behave to you?

Their behavior was horrible. Their brutality and arrogance was horrendous. For example the way they spoke with us. We were not allowed to mention our family members. We could not say mother or sister. We had to say the whole name, which sounded like we were talking about a stranger. Their brutality was simply terrible. They used to take me up by the elevator to be questioned. I could see the Střekov rock with some white slogan on it, probably, "Hello from the Communist party." The window was usually opened during the interrogation and I could see that rock. I can tell you that more than once I was thinking about jumping out of that window, but one has the self-preservation instinct. They put handcuffs on our hands and moved us from Ústí nad Labem to Prague, Pankrác prison by a paddy wagon, which had only small windows so we got in through the back door. It was a long journey, you know, and some of us needed the toilet. We were literally peeing under the machine gun. At the end of the day we were not shy anymore so we did not mind them watching us. Before Prague we had to change from wagon to tatraplan car and they blindfolded us. In Pankrác we were put into a holding where we could wear our civilian clothes. When they arrested us, I thought that it would be for a fairly long time, but I was an optimist and did not expect it to last for so long. Apart from the suit, which I was wearing, I took a black warm coat. I was really happy that I did, and I used it as a blanket – especially in Pankrác since there were not enough of them.

Did you experience any confrontation?

They confronted me with one man – a priest, František Blais. The examiners shouted at me, "so you say that your mother did not know about you helping people crossing the borders!" I wanted to protect my mother, because if they had arrested her, my grandma would have stayed alone, so I had to deny everything. They told me, "You may change your mind." I was blindfolded and did not take the cloth off my eyes, but I knew that they would beat František Blais. He took a real beating. He confirmed everything, but maybe he did not recognize me, yet I still recognized his voice. My mother stayed at home even though her life was quite tough, but she was there together with grandma, which made things easier.

How was your trial?

First I thought that everything would be solved by the court. I imagined that I would have to swear on some crucifix, but all the crucifixes were already gone. I was such a naïve prisoner. Our trial was open to the members of our families. I could see my mother, my future husband's parents and the wives of my accomplices. There were eleven of us on trial, but I was the only woman. The trial took place on 27th and 28th November 1951. Communists arrested their own communists that night – the Jewish group of Slánský, Goldstucker, London and the others. They told us the proposals on the first day, but the fact that they arrested that Jewish group caused lighter sentences on the next day. So our group got 15 years. I got 13, then someone else got 12, 11, 10, 7 and one got 5 years. After the trial, before they took us underground, I looked back at my father and the people I knew. The police officer told me off for doing that, but I said, "I will always be part of my family, whenever and wherever!" He reported me. I started the next day with my punishment. I got ten nights on a hard bed and half-portions of meals in solitary confinement in Pankrác.

What was solitary confinement in Pankrác like?

There was a wooden bunk-bed...a plank and gap, plank and gap with no mattress on it and bedbugs everywhere. Every evening you had to report your name, number and so on. The officer asked me, "Do you have it with or without a lid?" First I did not know what was going on. There was that toilet embedded in the floor and I think there might have been rats. At the end the officer gave me the lid, so I covered the toilet and fell asleep. I did not finish that punishment. Two or three days before the end I was taken away and moved to Kladno. They probably needed some extra prisoners. We never knew where we were going, but the sign on the bus always said "tour." We left on 6th December 1951, on Saint Nicolas Day.

What happened in Kladno?

In Kladno I worked in steelworks in a smelting plant. There were cranes with some liquid alloy moving above our heads and big pots with some boiling hot stuff. It looked like hell. It stank very badly; even a slice of bread you had in your pocket got stinky. I worked on a machine where there were some long poles and I had to estimate, whether the poles were straight or not after it went through some other machine. The civilians were not nice to us there; they were brutal, vulgar, and spat on the ground when they saw us. The prison officers did not have to take care of us so much because the proper communist workers did their jobs for them. I got a really bad migraine in January. I felt so bad that even a police officer took pity on me and took me outside to get some fresh air. Then they changed my position. I had to dig out metal chips, using a pickaxe. I worked together with another prisoner, Mrs. Stará. We had to dig the chips out and put them in carts.

When did you have your first visit?

I had it in Kladno. The visits took place by a big wide table. It was all very strictly observed. My grandma came. She was a tough and brave woman and she brought me a homemade pie, but the prison officers did not want me to have it, so she said, "Eat that pie." So I ate the whole pie in front of the officers' eyes. She also brought some photographs from which I stole one for myself. It was a little photo from the last New Year's party in our house. In the prison we used to wear jogging pants with an elastic band around the waist, which was very suitable for hiding things. I showed that photo to one of my friends, but I am sure she did not put me down. I only had a few friends there, but they were good ones. I think someone else must have seen it and told an officer. They came to search my cell, but I hid the photo very well, so they did not find it. Soon after that, in February 1952, they took us to Jilemnice. No accommodation was ready for us. It was only a small prison with two or three little cells. It was only made for escorts, not for staying in. Later we lived in a factory which had already been closed down. There were bars on the windows and a kitchen in the ground floor. Every day we walked under surveillance. We worked in a Technolen company, which was about 15 minutes away from where we were staying. We spun the flax there. So I was in Jilemnice from February 1952; I stayed there over Christmas; and in January 1953 they moved us to a different workplace where we worked with hemp; and then they moved us to Varnsdorf. That was a labor camp where we worked only at night because the civilians did not want to do the night shifts. Most of us ruined our vision there from working at night. We were in Varnsdorf when Stalin and Gottwald died.

What were the prison officers' reactions to those events?

We took a different way to work and somehow felt that the female prison officers were scared of us and did not know what was going to happen.

And did you know that Stalin and Gottwald died?

Of course we knew. The Czechoslovak Army practiced their parades and marches under our windows and shouted the news to us. We whispered the news to each other on the way to work. For this reason they decided to concentrate all people sentenced to 10 or more years to one place and they sent us quickly to Pardubice. I arrived there on 19th May 1953. The weather was hot in those days and we were all thirsty. They told us to stand on the small yard facing the wall, the sun was shining strongly on us. The chief of the Pardubice camp came and told us that none of us would leave and that we would all serve our sentences. All of us were sentenced to 10, 15, or 18 years.

Could you please describe the prison in Pardubice?

There were masonry buildings A and B, which were built during the reign of Marie Teresa, and a big administration building by the pavement at the edge of the prison. The prison looks totally different today. The A building cracked during a detonation in Semtín[5]. We lived there for a little longer. The building was supported by wooden columns, but they were afraid we would die there and built new quarters – Blocks C and D and Block E next to B. The C and D blocks were full of rats after one week. They were very wet and mildewed inside and there was hoarfrost in the winter. They stopped using the A building and moved us. Before those new buildings were finished, they emptied the big storehouses of the prison, put the straw mattresses on the floor and moved us in. There were sixty of us and we had only one toilet, which was the most private place from everything. The hall was very messy because there was one mattress right next to another. We could hide the cabbage we stole from the gardens right next to our mattress. The years went by in the Pardubice labour camp. Not only was it necessary to adapt ourselves to the regime, but also to make our own little private space. When I am thinking about it now, there was less than one square meter per person. There were 12 double-beds in each cell; it was a very small space, but we did not get on each other's nerves. We used to exchange things, and for example I got a little stool, which was like a treasure to me. I also got a little wash-bowl which was thrown out during each search, but I always found it and brought it back. Each of us had our little hiding place, our little secret, our life. Each of us had to somehow escape from reality in our own way. We had to learn to live a double life, to make our plans and dreams.

What were you thinking about?

I was thinking about my future life. I planned a family and was also thinking about things that happened. In my imagination I walked on trips, travelled and remembered my life. I would say that a prisoner relives the life he has already lived. You remember everything from childhood, and you remember people who were important to you. It is not that you would judge your life since you cannot change anything, but in prison you appreciate the fact that you were able to live your life and enjoy it. I regard that as a beginning of humility towards life and towards higher values like family and friendship. I survived in prison thanks to memories of my life, but without getting stuck in the past. You can't do that; you must have your daily routine and daily life. There were different events happening around us – we had visitors, letters – and each of us lived our lives inside. There were things happening in our homes, like a big loss or pain in our families, and we were not able to help – to go to a funeral or visit our ill relatives – and so we comforted each other and made ourselves happy. That helped a lot.

Did this fraternity work only among political prisoners or also among criminal and political ones?

There were only a few regional prisoners among us. Time to time they moved and mixed us, so murderers also appeared among us. I shared a quarter with one Slovakian murderer, or there was a small illiterate gypsy in our cell and she was allowed to have a child's reader, and that was a big thing. We did not even have papers or pens. I would say that there was strong solidarity among us, the state prisoners. The regional prisoners tried to assimilate. I did not experience that, but the women who were not granted amnesty in 1960 and stayed longer became a minority and I can tell you they went through hell.

I lived together with a murderer who adapted herself in all the ways. When any of us had visitors and brought something back to the cell, she would divide it into parts and put one part on each mattress. The murderer did the same. She was jealous of her husband and killed him, but the whole family used to visit her. She always got sweets and shared them with us. I was not able to eat it because she touched it with her hands – with hands that killed a man. I pretended that I had eaten it and liked it. We had to get on well with each other. That was a kind of unwritten prison law. You simply had to adapt yourself. We were all in the same boat.

Did you meet nuns in Pardubice?

They were there, but they separated them from us for some time. That was the biggest mistake they could have done. They did it on purpose because they wanted the nuns to be separated from us. The nuns were full of discipline and humility, so they were thought to be dangerous to the other prisoners. Politically prominent prisoners were isolated as well. That is how the two parties of HRAD and VATIKAN originated. Later those isolated prisoners were mixed and moved back to normal cells.

Could you please tell us something about the hunger strike in Pardubice in 1955?

It was very interesting because the hunger strike spread like a Chinese whisper. There was a new female prison officer in those days. She was not introduced to us, so we did not know her name, but everybody called her Elsa Koch – a prison officer from the concentration camp from the Second World War. We were on that hunger strike because of her. At the end she was removed and that was the end of the hunger strike. We were on strike because of the brutal treatment of the prisoners. Those of us who took part in the hunger strike were forbidden to get letters or visits for three months.

Would you be able to remember the Hammarskjold event, when women from HRAD sent 12 letters to the General Secretary of OSN?

It was in that time women from Hrad asked for paper and pens, because we were not allowed to have them, and sent those letters. I don't think that the letters were ever sent. No visitors came after that, never mind international ones. The answer to the question about the number of political prisoners was that there were only two. They counted in Fráňa Zemínová[6], who was a national socialist and I think the other one was Antonia Kleinerová[7] who was a national socialist too. We did not even exist to those in power.

Did you, the women who did not take part in that event of 12 letters, feel strange? Did you actually know about that?

No, we did not know anything in that camp, because the women from Hrad were isolated at that time and so we were not in touch with them. They even had extra walks, but later it spread around the camp very quickly.

What did the visits and correspondence with your relatives mean to you?

Over the course of time I would say – even though it might sound as self-praise – that we were all very brave. We simply lied. We were not allowed to talk about many things, so when we met our visitors we usually took delight in their civilian clothes and voice because we could not shake their hands. The bravery of our visitors was very important too. My brave grandmother or mother used to visit me a lot. And I must say that none of them ever cried. You could not say any names, maximally the first names, so we usually talked about flowers, plants and domestic animals. And letters? We were not allowed to have paper or a pen, but we were allowed the letters. They gave us A5 size paper with the camp's letterhead. We called all the letters essays, because it was usual to start writing about your fantasies or we wrote a whole letter about a bird. On the other hand it was also important what the writers told you. It was actually better when they did not tell us much because we were absolutely powerless and unable to help.

I got letters from my family and my fiancée. Those were love letters, which were censored twice. First in the prison where they were sent from and then in the prison where they were sent to. Talking about Pardubice, I must mention a big wooden box. We were supposed to put letters there we already read but the prison officers had no chance to keep up with it because the letters had no numbers or anything. They went through censorship and were opened when we got them. Then we had three days to read them and had to put them into the wooden box. I had never put any letter from my fiancée in there. I just could not do it. I had them hidden on my body or behind a beam. It felt like reading a very old calendar because the things written in the letter were already things of the past, but they were handwritten, and I could still feel a kind of fluid coming out of it.

What were your relationships among the female prisoners like?

I think it was easier for us than for those people outside. We were there together. There were only a few criminals, most of us were state prisoners and I swear we never argued. We sometimes had different opinions on things, but we always somehow discussed them and were convinced or not, but we never argued. Even the fact that we called each other "little girl" when we did not know a name shows a lot. We all had very good relationships.

What was the life in the labour camp in Pardubice like?

We were constantly at risk there. It was forbidden to go to a different cell or block. Sometimes we wanted to talk, let the others read a letter or did some craftwork and needed instructions. Many beautiful things originated there. We did everything secretly. For example we boiled horse's bone until it was white, then secretly got a knife from somewhere and kept carving for weeks. Unfortunately they were suddenly all gone. The prison officers probably took some of those things as souvenirs. There were bracelets, embroidery, etc. and they were all gone. Each of us could do a different craft. Then we would give our products to each other at some special occasions, for example at Christmas. Not only soup or biscuits from the shop[8] but also handmade things worked as nice and precious gifts. We always hid our presents in different places and lost them during searches.

Many prisoners, not only men, but also women, remember a so-called “prison university.” Would you be able to remember it as well?

Yes, those were walks in the yard. We would make groups according to our own will. We used to walk in our groups. Each of us knew different things and there were also women who were lecturers at universities. Some of us were deeply religious and were able to say long prayers, which I would have had read from a prayer book. So we usually joined the group, which would teach you something or where you talked about things, which made you forget about the prison. We used to walk around pretending that we were talking, but one of us usually gave a lecture on various topics. When we came out of the prison we used to say, "The prison was actually my university." I was always interested in psychology so I secretly studied characters and the behaviour of other people. It was a great opportunity to share a cell or a walk with people who were interested in something or wanted to pass on their knowledge. This was how we got knowledge, that was precious and helped you forget about daily life in the prison. One woman asked me once to describe a day in the prison. It was not easy at all to do so. Someone who has never been there would probably say that the life there is very monotonous. There was a regime, which you had to follow from dawn to dusk. That is true, but you had time for your ideas and that time cannot be taken by anyone. You basically lived a double life. The days there were not monotonous because there were constant transports, searches, letters and so on.

What about the hygienic conditions in Pardubice?

They were horrible from the beginning to the end. We got used to cold water after some time. We dealt with water like ladies in Africa. Once we exchanged a wooden dish and then each of us grabbed it from one side. Those things were forbidden but tolerated. We asked for hot water in the kitchen and then used that one load of water to wash our faces, hair, then clothes and then the floor. There was one kind of soap for everything. The wash room was horrible, it was dirty and mildewed. We were strictly forbidden to wash or dry our clothes. Some chief arrived one day and we set our conditions. We wanted to wash our clothes and finally we were allowed to do it.

Do you remember any cultural activities?

They started showing films. I do not remember which year it was. But we never knew what was going to be shown, and that was the purpose. The films were voluntary, so when we went to watch them, they had time to search our cells.

I remember that once somebody told us about a beautiful film that they were going to show. It really was beautiful, but when we came back to our cells, they were in a mess, and all our things were jumbled – sugar, straw from the mattresses, everything on one big pile. They also showed a Soviet film a couple of times, but I do not remember its name. I saw it more than once, but always had to finish it because they did not let us out.

Do you remember the day when you got released?

I was released before the amnesty in 1960. The communists knew that the changes were coming so they started releasing people in 1959. At the end of 1959 they called me into the administration building. There they asked me some questions, but I was not successful. I think they would have released me, but I did not reply in the right way. So I went back to the camp and had my ninth Christmas in the prison. My family applied for my release, but I never asked for it. They called eight of us again in January 1960. I did not answer in a different way. They decided to release me on probation. I still had four years to go, but the probation lasted for eight years and that was very inconvenient. Nobody wanted to give you a job, but you had to work so you had to accept some inferior one. We did not know about money or means of transport; we did not know that the third class did not exist in trains anymore. We felt like we fell down from the sky. One censor took us to the train station. We called him Cap. I did not have any civilian clothes. I had to borrow them from Vlasta Brhelová. I looked like a scarecrow. The censor bought us the tickets and told us the times of our trains. We were like children.

How was it when you returned home?

I came to Teplice early in the morning. My mother worked in a Hotel Thermia. I asked one dispatcher to call the hotel and ask if my mother was at work. He called and found out that she was there. I walked through Teplice, a hilly town, and as I walked up Leninova Street, I had problems catching my breath. I gathered all my courage and entered the hotel. My mother took a day off and went home with me. My father was not at home, but my grandmother gave me a warm welcome.

When were your father and fiancée released?

My father was released in 1955 and my fiancée was granted amnesty in 1960. I never believed in that amnesty. Some prisoners were kept alive thanks to the vision of amnesty, but I never hoped for it, even though I was such an optimist.

How was it, to come back to normal civil life?

Coming back to civil life was very difficult even though I had a good family background. It was a bit easier thanks to my mother, who told me to stay at home for some time. I got a new identification card and did not go out of the house. It was not easy at all to rejoin society. Nobody would believe me, but I can tell you that I missed the prison – I mean, the people there – because there was that support and assurance. I did not know what to talk about with other people. I think that the mindset of the prisoner cannot be changed from day to day. You cannot suddenly think and talk about normal things. Many times I remembered the words of my co-prisoner Zofie Slovackova. She used to say, "Do you know what I would like? When we are all released, I would like us to live in big villages or small towns all together – all the prisoners together." She was right. It probably would not work that way, but living somewhere with each other would have been good. It would have been lovely to live in mutual help and friendship.

When you look back to the time in the prison, could you tell me what it gave you?

It gave me confidence, and from the political standpoint, it gave me the anti-communist stance. I will never, ever support their party. I cannot understand that some young people support them and their program. I know that they lie.

Have you ever forgiven the communists for all the injustice they did to you?

Once I gave a lecture in the hall of a grammar school in northern Bohemia together with Archbishop Karel Otcenasek. I let him start, and he started as a true Christian with a speech about forgiveness. I knew that he had experienced a very hard time in prison. Then it was my turn to talk, and the first thing I said was that I felt like a rebel standing there next to him. I told the students that nobody ever said sorry to me. The archbishop said that we should forgive, but should not forget. Those are very important things. Personally I have never forgiven them, because they stole a big part of my life. I had my plans and ideas, and I lost them, and they can't be taken back. I wanted to live a free life, travel, and do things to make myself happy. And they spoilt it.

Thank you very much for this interview.

[1] Teplice – a town in the north of Bohemia.

[2] Calling from London – During WWII, the BBC radio station broadcasted three fifteen-minute news programs in the Czech language. Listening to the foreign radio in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was punishable under the sentence of the death penalty.

[3] Post-war Transfer – The post-WW II expulsion of the German people out of Czechoslovak border area into Germany and Austria. About 3 million people were deported between 1945 and 1946.

[4] The Communist Coup in February 1948 in former Czechoslovakia – see “history” section on our website.

[5] Semtín – a town close to the prison where there was a factory.

[6] Fráňa Zemínová – a Member of Parliament who represented the Czechoslovak National Socialist party from 1918 to1939. In fall of 1949, she was arrested at 68 years old and tried in a show trial with Milada Horáková. She was sentenced to 20 years and released in 1960.

[7] Antonie Kleinerová – a politician who represented the Czechoslovak National Socialist party as a Member of Parliament after WW II. In 1949 she was sentenced in a trial with Milada Horáková and given a life sentence. She was pardoned in 1960.

[8] Prison Shop – a small shop where prisoners could buy basic hygienic items for prison money and a limited selection of food.