Gustav Bubník

Interview with Mr. Augustin Bubník

"Jáchymov was the suffering of a nation that can never be forgotten." ~Augustin Bubník

Interviewer: Tomáš Bouška

This interview's English translation has been gratefully edited by Ms. Olivia Webb.

First let me ask you about your childhood and place of birth.

I was born on 21st of November 1928 in Prague, so in the zodiac I'm actually in the last week of Scorpio. Scorpios have always been proud fighters and are also able to get together and do the best thing in every situation. According to my mom and dad, when I was born in 1928, there was terribly frosty weather. Even while they were taking me to my baptism, they thought we would freeze. So I was probably predetermined for frost and ice hockey. During my childhood it already proved true. My father was a butcher and worked in a slaughterhouse. My mom was a shop assistant at a butcher's. They both came from Southern Bohemia to Prague and we all lived in Holešovice in Prague 7. My mom was a big Sokol fan[1], so she used to take my sister, who was two years my junior, and me to the Sokol training area at Libeňský bridge. There was an ice-rink created each winter. There we actually started to learn to ice skate. Then I found out that there was ice near our household, at Štvanice Island, where you could ice skate and play ice hockey.

When did you start to play the major league hockey game?

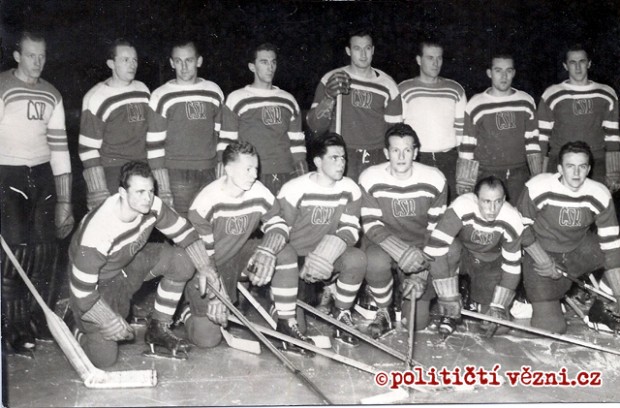

After the war, the major leagues were the Olympic games in 1948, where we pulled off and drew the game by tying Canada, with a score 0-0. For Canada it was a shock. Up until that time they kept coming to Europe and beating Czechoslovakia. The first match against Czechoslovakia in 1911 was 30-0 and then we were only losing by 20 and later a 10 goal difference. Canada was coming to Europe for a World Cup and it was a vacation for them, because they were beating everyone around. It was a shock for them when we ended up 0-0. After the end of the Olympic games there were conflicts between the captain Vladimír Zábrodský and the head coach Matěj Buckna. Coach accused Zábrodský of establishing the wrong tactics – that we should have played offensively, not defensively. Buckna kept disputing that each of the players had a big chance and opportunity to score a goal, and the Canadians as well. Thank heavens we had a great goalkeeper, Mr. Modrý, and the match ended 0-0. We got an invitation to Canada, to measure our strength against some Canadian teams at home. At that time there were only 6 professional hockey teams playing in Canada.

What constituted your "seditious" activity?

In that post-war time they were flaunting us as the most popular European hockey team from LTC Prague[2]. Every New Year we played in Switzerland in a tournament called the Spengler's Cup. Right after the Olympics in 1948, the whole team got into a conflict with Czech immigrants from LTC Prague who were already living in exile[3] in Switzerland. The people in exile asked Mr. Zábrodský, as a speaker of the team, to organize our stay there. That would mean the whole team would stay abroad, playing under the name of the Czechoslovakian national team-in-exile. We would play in Europe, especially in England, and in turn would advertise the image of this team. At first, Mr. Zábrodský promised everything. Then they didn't give him double the money as they had promised, for each player, and so he refused the whole thing. There was even a vote, where 8 of the players were for returning and 6 for staying. In that moment, one of the Zábrodský brothers and doctor Fáma, who was a lawyer stayed in Switzerland. He was then 26 or maybe 28 years old, but knew well he couldn't come back to the country. They were spokesmen for this organization and that was why they knew there was no return for them. We went back and that was the beginning of everything.

Did the repercussions start soon after you returned to Prague?

Not yet. In 1949 we became world champions in Sweden. All of a sudden we beat Canada 3-2! That was the first victory for Czechoslovakia against Canada. The score was 3-2, and if I remember well, Konopásek scored the first, I scored the second, and I think the third was Roziňák. Grand total, we won 3-2, which dethroned Canada. When we came back, the government welcomed us at the train station in Prague. There was the Prime Minister Zápotocký, and other ministers. They greeted and congratulated us in a private government lounge in the railway station. The train station was full of people.

But in 1950 they didn't let us go to the next world championship in Great Britain. They wanted us to proclaim that we would forego participation since Czechoslovakian reporters didn't get visas to travel with the delegation. In the meantime, my sister, who worked at a state office here in Prague, got in touch with friends from the British consulate and photocopied the problematic visas. The visas were available. All the reporters had to do was pick them up on Saturday, but they never came.

So we all got together immediately at "U Herclíků." That was a little pub by the National Theater in Prague, and the owner was the brother of a Sparta[4] player, Zdeněk Ujčík. It was a pub where we, civilians and soldiers, could meet up. We drank and ate well there. I remember, we dropped our luggage home on the way from the airport and by 5 p.m. we started to hang out. There were already some people inside. There was a bagpiper who also played the harmonica. The whole time, we sang various songs about sports or Prague. You know – memories. And then, when our merry-making was at its peak, and it was revealed why we didn't fly to the championship, we all felt pretty bold. I can sincerely admit we swore a lot, and from time to time, we would also run out into the little square and yell, "Death to communists!" or "We will not let you cut our wings, we will reveal the truth!" In that moment we heard the radio reporter Edmund Koukal explain the reason the hockey team didn't leave for the championship. He said exactly what he was told to say: the hockey team forgoed participation because the reporters didn't get visas. So we called Mr. Laufer immediately, saying, "Come here, we will tell you the truth." No, he didn't come. We called Koukal right after the commentary to come to us and he answered, "Guys, I will not come." When merry-making was at its peak and we were already very drunk, we started to sing some songs about the ex-football player Vlasta Kopecký. It was a Slavia[5] song. Instead of Vlasta Kopecký we sang Venca (Czech name Václav) Kopecký, who was a minister of schools and sports. When that hit its climax, I was walking by with Roziňák and suddenly two men got up from one of the tables and caught us. They told us we had to go with them.

What are your memories and what comes to mind when I mention "domeček"[6] at Hradčany?

The time I lived there was from April 15th to the beginning of May. I was transported to holding at Pankrác when they finished the investigation. That was the worst time in my life. I was a young kid, having fun with all those things, thinking that nothing bad could happen to me. Maybe we would get a punishment for the disturbance we caused in the pub, but everything that happened afterwards – all that investigation into the whole case – and everything that was rolled onto us was really cruel. Of course, the worst times were those when we were in the hands of Pergl[7], the boss of the "domeček." The most terrible thing was when they took us to the general staff at Dejvice. It didn’t matter whether it was in the morning, noon, evening or at night: everything depended on to what extent the investigators were in a mood to talk to us. The worst was his abuse and treatment in the "domeček." The cruelest was a dungeon cell under the staircase where he put me and the other boys once he got the command, though I spent the most time there. It was dark and there was no daylight, no bulb. It was a hard-packed cell, wet and closed. There a man was like a mouse in a hole adrift until they brought coffee or a piece of bread, if anything.

Those were horrible things. From the moment we went into the "domeček" he used violence, a truncheon, and a cat o'nine tails with little bullets. He would hit a person with that from the front, from the back. I fell down many times, and he behaved like a beast that would only be satisfied by that cruelty on us. Of course, his expressions and everything made you worry about your own life. Many times he led me to the interrogation pointing a gun at me. I didn't know whether it was full and whether it was on safety, but he said, "Make another step and I will shoot you like a dog, you seditious bastard" or "Will you speak or not?" The worst was when the investigators didn't get what they wanted out of me. When I couldn't confess what they were suspecting of me, then the nights and days were bad. The truth is that they had to give us some laxative in the coffee, because we were starving. I remember Tonda Španinger saying once, "If I could catch a bird sitting on the ledge, I would eat it." It was that brutal over there. So in that "domeček" there were six of us, six soldiers. The guards weren't men, they were beasts, who were our age, maybe a little older. They kept walking in corridors, kicking the doors and we had to either do push-ups or knee-bends or run around... briefly, they always wanted to crush us so the investigators would get us in such a state that they would be able to do anything with us. I remember getting to Pergl's office and I saw various instruments hanging on the walls...

Once they gave me a metal belt around my head and kept pulling it tighter and tighter, so I thought it would squash my head. They tied your arms together so you couldn't defend or fight back and they did whatever they needed. I actually lost thirty kilos (66 pounds) while I was there. I came in with a weight of eighty kilograms (176 pounds) and when I was left I was nearly fifty kilos (110 pounds)... they still wanted to prove that I was guilty – that I was the head initiator and traitor, and that it was me who persuaded others to stay in abroad. I always wanted a confrontation. When the investigator declared that Josef Jirka said this and that, showing me his papers, I said, "No, I want you to put us face to face." Even once when we were going by a car with Jirka together to investigation process I said to him, "What the hell were you saying in there? That isn't the truth at all." He was absolutely psychologically damaged. They could and did anything they wanted. We would have signed anything. So they took us to the office to be confronted. In the car, when I said I didn't tell him anything, he started crying and totally broke down. I knew it and I believe that Pergl not only scourged us, but also high ranking soldiers of the foreign army and generals. Pergl really scourged all of us. He wasn't a human being, he was a hyena, reigning there, and he did exactly what they wanted him to. He was getting people ready for the investigation process. When all that was over, I was really happy I got to Pankrác and I was waiting to go through the investigation there.

How long did the "domeček" situation last?

It was from March 15th. They took me into custody on the 13th then they took me to the fifth department by the Saint Nicholas church two days later, the one at Malá Strana. Then Lietenant Hůlka came to pick me up In addition to being in the army gym club in Chuchle, he was also a member of OBZ[8]. Also this, "Dry Linden" Pergl was there. From Saint Nicholas they took me to the "domeček." So I was there from March 15th. By the time I was traveling back, a flower called “golden rain” was in bloom. I remember it was May Day, because I heard the big celebrations on the Ring Square. I was there until the beginning of May, when they took me over. So it lasted seven, maybe eight weeks.

The six friends, can you name them?

Who was at that "domeček"? Of course I can, it was me, Kobranov, Štock, Hainy, Španninger and Jirka, all six of us who were on the national team and who were nominated for the world championships in London. In fact, we all were soldiers. Some in the basic service, some who for two years had already played hockey for the army sport club. We represented the army and we had the basement in Chuchle Station. We lived in a villa and commuted to the stadium at Stvanice to train and play. So there were these six soldiers, but some of us left there at different times. Not all went as late as I did. I think that I was one of the last ones who was moved to Pankrác[9].

Nevertheless you were one of the youngest ones.

Unfortunately, and of course I was really a naive young boy. Today I can see that. I didn't have a clue what was spreading around and what Communism was.

How old were you at that time?

In March of 1950 I was twenty-one and a half. I wasn't even supposed to start my military service yet. I went as a basic soldier because my best friend Vofka Kobranov went as well, and we played two years before that on the national team. So he talked me into it. I went into the military service a year earlier than I had to. I wanted to be in the military service so that we both could play for the army sports club.

Out of six, was there anyone who didn't confess?

For sure Jirka confessed everything that they knew on him. For sure Hajný confessed. He even got only one year of punishment because he confessed that he had plans to stay abroad. He was a really smart and intelligent kid. He was also doing track and field events, and was connected with Václav Mudra. Mudra became the biggest chief of OBZ after 1948 because he was an athlete, but they did sports together in Slavia. So it was possible that Mudra helped him get somewhat off the hook or out of the whole thing. So for sure Jirka confessed everything that he did, what he smuggled, and everything else. Španinger didn't have to confess about anything since he was in the whole case by chance. He wasn't even in Switzerland with us where we voted whether to stay there or not. Štock was also supposed to fly with the national team for the first time in his life; and, from the paper, I later found out that Štock even said those things that he didn't have to talk about. So they got him on everything that they wanted. Vofka Kobranov didn't confess for sure, and neither did I.

Just for interest, how did you vote in Switzerland?

In Switzerland the whole thing finally collapsed when the immigration group didn't convince the whole team to stay and play as the Czechoslovakian team-in-exile. The main initiator and speaker was the captain of the team, Vladimír Zábrodský, who put the whole thing together. In the morning a few days earlier he said the team voted eight players for returning and six were for immigration. So the decision was resting on him, how he would decide. If he would decide to stay I am sure the other eight players would have stayed as well. Maybe some of them would have returned, because at that time it was really hard. For a person who wasn't even twenty-one years old yet, parents had to give security. That meant that if we stayed abroad, our parents would be arrested, and the whole family would be liquidated. The other ones who were older, like Konopásek, Roziňák, Trousílek and the others, lived either alone or had their own families for they were just older then us twenty year old kids.

Were you for returning or for exile?

I was for returning because I didn't want to get my parents into such trouble.

When you moved from „domeček" to Pankrác, what did they sentence you for?

When we got to Pankrác I was in a cell with two other prisoners who were also waiting for their hearings. That wasn't a solitary cell. There were no more beatings, or fear that they would come up with further accusations. For me, the worst was the investigation when they wanted to beat out a confession that I was giving messages to a Mr. Bowe. He was the boss of the American Embassy here in Prague who would give out the entrance visas to Germany to all four zones, whether it was the American, British, French, or Russian zone. That was the man Mr. Modrý introduced me to. He would come to hockey games and he played golf; his wife played golf; and I really started a friendship with them. They used this as a pretense that this Mr. Bowe would inform me and that I in turn I would give him other messages or info as to what was happening in the army. Yet, in my army nothing was happening. We played hockey. When I would tell them this, they didn't want to believe it and they still insisted on a confession about what messages I would give him. He was supposed to be the main initiator – a person who would persuade the whole team to immigrate, which wasn't true at all. I later found out that in twenty-four hours he was deported out of the country because he was accused of espionage.

So when we came to Pankrác it was already a little different there. For me it was terrible what I was learning there. Other prisoners were giving me advice on how things go there, like when breakfast and lunch were brought. We would go for a walk once a day out on the square between the blocks of Pankrác prison for half an hour. A man could learn some things there and would be given other advice from other prisoners. The worst was when they told me about one time when they hear a murmur early in the morning. I actually came right before the execution of Milada Horáková[10]. Of course the other prisoners knew those who were there for a couple weeks or months and learned the prison routine. The breakfast lasted longer than usual, so we watched out the windows onto the square to see whether something was happening, but Horáková was executed off out on a corner. It was terrible for me when I saw that. We also watched out through a little half window that we tilted down. We were not allowed to do that, but a man could look into the reflection and see that square. The awful part was the view of people called "řetězáři" or "chainers." Řetězáři were the people who had tried to escape. There were also people called "provazáři," or "ropers.” "Provazáři" were people on death row. The other prisoners, I don't remember their names, were counting them. They knew how many there were. When one all of a sudden went missing, they would say, "Oh well, so another one has been taken away, hung, or sentenced." These "provazáři" were unexceptionally down in the cellars – dungeons where they would await execution. "Řetězáři" were people who had escaped from labor camps who actually had leg-irons that chained them to the wall. That really existed. In that cell the prisoner couldn't move. He could just sit on a little chair and not do anything else. When he needed to defecate, he was to use a little bucket. When they would go on their daily walk, they had to hold their chains behind them because the leg-irons had protrusions, so they had to walk with their legs wide apart, otherwise they would trip and fall. I can tell you that was a terrible sight, for me, a twenty-year old kid, to see that something like that existed.

What happened after that?

That's how I lived through that time until I had a hearing at court in September. Before that they would call, come to meet us, and then continue calling us until we got two lawyers for representation. Roziňák and I had a man named Lindner who was a really tough lawyer. When he read everything, all the papers, he said, "They can't sentence you for anything. You can just get something for the disturbance in the pub. Maybe you will get a year or two. They will sentence you and put you into a military prison. Yet, other paragraphs that are here like spying, high treason, disrupting the socialist state they cannot prove because there is no proof and it's all just fiction." Finally there was a hearing. The first day we all thought that through all the contacts with our families and through our lawyers, that our wives and kids would be in that big hall. We were having court in that huge hall as Horáková did and all those other cases. We thought that we would see our relatives somewhere, but when they dragged us through the corridors no one was there. We came to the reception hall and there was also no one waiting. The first one to be called in was Mr. Modrý, who testified for almost half a day. In the afternoon it was me. I was the next one. Our court was for two days actually. We were very surprised that the court wasn't a civil court. There were twelve of us, six civilians and six soldiers. We learned from the papers that we didn't have a civilian court, but instead a military court. They also called the process to be top secret so people who had nothing to do with that case could not be present in that hall. Whether it was associate lawyers or the master of the court, we saw just one person that I remember really well. It was the communist editor, Václav Švadlena who was writing for newspaper "Rudé právo"[11]. He was the only one who had free access to this whole process.

What was your perception of the whole court process?

We thought it would be easy and we would be acquitted of those charges. When we saw that the head judge started dealing with our charges we still thought we would get some leniency. The second day Bóža Modrý and I were sitting there the whole day and the others were testifying, Roziňák, Konopásek, Macelis, Jirka, Štock, Španninger and the pub owner Ujčík, who got three years for not stopping us from the disturbance. When we were waiting for the final sentence, we were all standing.

What were the final verdicts?

We heard the speech of the judge as we were all acquitted from the death penalty, but we were each given sentences: Modrý 15 years; I, 14 years; Konopásek, 12 years; Roziňák and Kobranov, both 10 years. Then it was 6 years for Jirka, I think; 3 years for Červený; 2 for Macelis. Hajný got a year and Španinger got 9 months. The pub owner Ujčík got three years. All of a sudden we were standing there completely depressed because we were standing up against something that couldn't be recalled. Of course after we consulted with our lawyers the five of us who were given the harshest sentences for high treason and spying immediately appealed to the Supreme Court. The five of us who had 15, 14, 12, and 10 years appealed to the supreme court[12]. We were put back into our cells and I remember such a funny story. When I came back to the cell, two of my cellmates were already both sentenced. One of them had twenty years and the other had maybe eighteen years, so we came and they said, "So how much did you get?" and I said, "fourteen". "Man that's nothing, you'll sit that on a razor blade," they said. I answered, "What? Ona razor blade? Fourteen years on a razor blade – that's not possible." They said, "that's how it's said here. When a person isn't hunged and he can walk away from the sentence and go on living."

What happened next after the court verdict?

We were waiting for a long time in the court department and then sometime in October or November they chased us out and loaded us onto a bus. The whole escort was maybe around thirty people. We were together, and I remember I was tied to the arm of big Červený, our goalie. They put us on the bus. The bus was surrounded by police cars. We left without knowing where we were going – whether it was a prison or a camp. Our cellmates had informed us that you can either go to another prison or a camp. All of a sudden we appeared at the prison Bory[13]. When we came there it was just terrible. The welcome process as we were walking in the corridors to the main square ... I think it was B corridor ... a big fiasco started. There was a guard who started yelling at us and calling us names. Some prisoners were even making fun of them, and Červený was also making fun of them; he was quite a joker. There they hit us with nightsticks and we had to line up, whether it was Trepka[14] or Brabec[15] and the other guards. During that terrible process we had to take our clothes off in exchange for a sack in which we found prison clothes and other items. The fun was, for example, I had pants up to my neck until they took it away from me and switched them with someone else. They put us in those stripes and in a little while someone else took us away. By the way, right after we came there, they took us upstairs into a room and took a picture of us. First they took our pictures in civilian clothes and then I got my prison number. After that they took us downstairs and barbers came and shaved us bald. During everything, very funny stories were made up. I remember that when they were giving us the stripes, Červený, who was a big joker, was asking, "Who sewed your clothes? They don't even sell such a suit at Bárta's shop." That was the most popular tailor on Na Příkopě street where the rich people had their clothes made. Of course he was hit in a second and punished. Another funny thing was when they shaved our heads. On my head I had a big laceration and you could see a scar. So Zlatka didn't forget to make another joke: "Well your head is sewed up together nicely. Everyone will like you," and he was smacked. The guards were slapping us here and there. So they took our pictures in civilian clothes, dressed us up, and took our pictures in stripes. I have all these pictures and when I look at them I must laugh. Then they put us into the dungeons where we were either in solitary cells or in pairs. There, real prison life started, and we had to conform to everything. When a guard kicked your door and he was demanding something, one had to do it.

What was your first experience with forced labor like?

Every morning they always threw a bag of dirty goose feathers into our cell. After that, another bag; we were in pairs. We had to strip the feathers; we had to learn to tear off the quill from the little feather and put this into a special bag. The rate of output was very high, and so was the bad smell from the feathers they brought. We had to strip all the stuff they brought.

I don´t remember exactly, but at one time it was about 33 dkg (7.3 pounds) and then they increased it to 60 dkg (13.2 pounds). A man from Bory described that in a book of memoirs.

If one didn´t do it, they didn´t get food. Work over there was really hard for people who had never done it before in their lives, or whose fingers were numb and so they couldn´t. Some of us were working and got so good at it that we were able to help a cellmate. When I saw I had about 60 dkg done and they didn´t come to get it – even though – it was after supper and we had a whole day to do it, I quickly helped my cellmate. They always took it away and never weighed it in front of you. So you didn´t really know whether you met the quota or not. You didn´t have a clue whether you would get a quarter of bread or soup or just some peas and barley or something else that they served. One simply didn´t know, and depended on the mercy or disfavour of the guards – whether they would admit it or not and whether they would feed you or not. Although it was a cruel time over there, and we lived through hard days and months, there came a day when they took us out of the dungeons and moved us from B block to another department. I think it was D.

How did it look like over there?

There were bigger cells – five of them, with ten pallets that were called beds. As we found out later, this department was called "Kremlin"[16] and there were about fifty prisoners, or ten people in each cell. There were a couple of "katers"; that means a couple of iron bars. From each of these bars, a different guard had a key. So one guard couldn't get through it alone; there always had to be two or three of them.

In that dim light there were people who we could call "the best of the Czech nation" – not only generals, but also politicians, priests, and officers of the Eastern and Western armies; the pilots who made up a British squadron; and the majors of Brno, Lenora[17] and other towns where they were taking people across the border. Among these ten people, life was different and again specific in certain ways. Before that you were just with one person and didn't get to see the others unless it was during the compulsory walks. We went to walk between the houses because the prison in Bory was built in the shape of a star. So I could see that there were others walking there too, possibly a friend or just a familiar face. We also went to have a shower once a week and that was it. When we got to the new department, to the "Kremlin," it had changed; there was a different way of living. We would get food; there was a corridor of servicemen who would bring us food. Breakfast in the morning was a quarter of bread and coffee, and then lunch was served in a tin cup.

Do you have any positive memories from this time?

I later recognized that I was in a completely different prison system in the “Kremlin.” As a young boy who didn't have a clue what was happening around the world, I learned a lot there. It was my first university. The people opened my eyes. The former commanding General would tell us about the western front. Pravomil Raichl, who was my cellmate and something of a mentor, kept telling me about Russia. How he escaped from a gulag[18] where there was such hunger that when someone died, others ate his body...when I heard this, my eyes were popping out of my head. Priests talked about what was done to them before the court. I was there together with one General Paleček, the head of the paratroopers on the western front who was sentenced for life imprisonment. There were a lot of generals and also Mr. Podsedník, a mayor of Brno who was sentenced because he was a national socialist. Next there was Červenka, a mayor of Lenora at Šumava district, who had stories about helping and leading people and big shots over the borders to Germany. There was also a member of the Lidová Strana party, Mr. Herold, who told us what had happened in Parliament after 1945: how they had arguments and then would go to drink together, no matter which party they were from. I was gaining knowledge there and they taught me everything – and in these cells we worked too. We couldn't go out to work, although those who had lower sentences could leave the prison and go to workshops. We were not allowed to go out, but they brought us various projects to work on, whether there were flags we had to glue on wooden sticks or snap fasteners brought from Koh-i-Noor[19]. There was a quota for everything. We would also clean silverware, which they stole from different chateaus and castles and brought to us in a decrepit state. We had to clean each piece with ammonia and a white chalk until it was nice and shiny. They even gave us sewing machines and we had to learn how to sew cables from cloth or leather. We worked with leather a lot there. We were making straps and parts for textile machines working with hemp; we had to bead rolls. Everything was under quota and everyone had to fulfill the quota as the food depended on it. So there were ten people who were already a group that would quickly work as a team. The most beautiful thing was on Saturday afternoon…I can no longer remember if it was at three or five o'clock… but they locked down all the bars and we knew that nothing would happen and no one would be dragged through an inspection until Monday morning. Always on Saturday or Sunday afternoon, one person from each cell would have homework to prepare a seminar topic he wanted to talk about. It was a little university there, but big training for a man. We were still waiting for the final word from the Supreme Court. We were still living with high hopes that the punishment would be reduced and that we might get only a year or two instead of fourteen years. So there was hope living in each of us that we would be released from prison.

When did it come, the result from the Supreme Court?

It was terrible that it was autumn and we were still in these dungeons, five of us who appealed were still sitting in the "Kremlin." In each dungeon there was one of us, Bóža Modrý, Kobranov, Roziňák, Konopásek, and I. We all went through that. It was close to the ice rink in Plzen so we heard each goal. They were playing hockey there and we were in the "Kremlin," sentenced to so many years. From that point of view it was horrible, to find out that it's the end of your sports life. I was just twenty and when I thought I would have to spend fourteen years there I would come out at age thirty-four and only be able to go and dig potatoes and not play hockey.

When did the statement finally arrive?

That hope was still living in us when all of a sudden they announced that the appellate court will be on the 22nd of December, 1950. So we were waiting to see what would happen. They came for us and dressed in prison clothes they put us in an "anton."[20] In front of us and behind us there were cars with machine guns and we were still hoping at least at this court we would see our parents and our children.

You hadn't seen them until that time?

We hadn't seen anyone at all, absolutely not. They took us again to that court and I remember as though it had happened earlier today. The chairman of the court was Mr. Kruk. Then they called us in. All five of us were standing there. First, a plaintiff spoke; and then our lawyers were speaking and pointing out the facts – that nothing had been proven. They were insisting that there was reasonable suspicion, but they had no proof and therefore there was nothing that they could sentence us for. Our lawyers were telling us that and we still believed it. But the prosecutor was a real bastard. He kept reading various protocols, even a statement from a woman who was a caretaker of a house we were living in where my father had a shop, a butcher shop in Podbaba[21]. This my father took care of this caretaker during the whole war; he gave her things to help her out. Because she was a secret communist confidante, his lady wrote about me – that I was the last root of a Golden Prague Youth that must be cut off. I rolled my eyes when I heard what people from my building wrote about me. What people who knew me and knew that I was a famous person wrote about me. So the plaintiff again put the worst on us, regardless of proof or confirmation from the court that it's standing on our high sentences, but we still hoped. I remember Dr. Kruk as though it was today, how his hands were shaking, sweat running down, and he was completely flabbergasted. This guy was certainly doing something that was against his will. His voice was shaking when he confirmed that all the sentences are confirmed by the highest court.

What ran through your head at that moment?

I remember that even at that moment, even Modrý, who still continued to play the hero, said, "Well guys the cage door just closed and we're inside. No one will help us now. " The supreme court confirmed the sentences of the state court and we knew that we couldn't do anything except live through that time or wait for a presidential pardon or else to be released on a two-thirds or one-half punishment for good behavior and satisfactory work. All prisoners fooled themselves into thinking that they wouldn't be there for their whole sentence and that they would get out earlier. That also happened later, when I got into camps in the Jáchymov area or the Příbram area. In every prisoner there was a little light of hope that their day of freedom would pop out. There would have to be a rebellion or a war and then we all would be released, or else we would be released on a condition reversed by the court or something similar. When we got back from the highest court on the 22nd of December, just two days before Christmas Day, I remember there were our parents, sisters and boys' children in front of Pankrác Hall, and none of them were let into the process.

Did you have a chance to see any of your relatives during this time before the final court decision?

No, but I have a little memory in my head from when we were coming to Prague. They took us in an "anton" all tied up together to the rail station in Plzeň. There we had a wagon with a coup reserved and surrounded by police so no one could enter. We went this way to Prague, and when we got to the main Prague train station, the train stopped on the first platform. They took us out from the wagon to a special government room, which still exists, and from there waited for another "anton" to take us to Pankrác. This car backed up right to the entrance and we went from the room, to the car, and then straight to Pankrác. Of course we went straight in so that no one could see us. While we were sitting in the government salon, we were allowed to speak even though there were secret police around. We looked at each other and said, "So guys, can you see this? One year ago, another train took us to the first platform. Here the government welcomed us. Zápotocký[22], all the ministers, and all of Prague were at our feet and today they took us to the same salon." I remember that so well, but I can't remember who said it. So we thought that not even a year later, we were something completely different for the nation. We returned the same way, to the salon, from the salon, to the train, by train back to Plzen, then into the same "anton" and back to Bory. We got back to the dungeons and continued to work as I've already described.

How did the daily routine of a political prisoner look like in a stone prison?

I was lucky: out of the fifty people who were transported there, I was the youngest one. Right at the time, one of the prisoners left who was on hall duty, and so a Commander Trepka had me do it in his place. I didn't know what that was, but they took me out and I found out that my boss was General Paleček, one of the biggest war heroes. He was a really good man who taught me all the duties of prison. All of a sudden I was serving food, pouring soup, and together we were putting food onto tin plates and putting them into the little windows where the prisoners would take them from us. This way I knew about everything that was happening there. Paleček taught me various tricks, for example how to take "moták"[23] from one dungeon to another. When we were pouring out the piss and shit, disinfecting the bucket and putting it back into the cell, guards were usually away so we could put in a piece of paper which had a message. When soup was poured in, and if I was holding a "moták," I blinked my eye and I dropped it in for the one I was giving it to. Then he knew he had a message. That was something amazing for me. I was also going to pick food from the central, so I saw the daily life in prison. That was nice and I can tell you at that time I cheered up a little, even though I had fourteen years without knowing how it will go on.

How did you get to Jáchymov[24]?

I can't tell you exactly when it was, but it happened within a year, sometime in 1951. Suddenly they started transporting us, probably canceling "Kremlin," because some prisoners were taken to Leopoldov. Others went somewhere else, and some of us were taken to Jáchymov. We came to Vykmanov by Ostrov upon Ohře, where there was the main gathering camp and from that one they divided us into different camps. In a short amount of time I was right next to this camp. This camp was called "L" and also a camp of death. Here the uranium ore was broken, split up, put into barrels, and sent to Russia. That was really a death camp. Whoever was there for a long time had really bad health problems from the dust and radiation. Some people didn't even stay there for a month and some people stayed two or three months, some a half year, and some had health problems for the rest of their lives because of blood decay, muscle decay, muscle or bone decay and so on. That was the worst camp. I was there for a short time, maybe a week or two weeks and I didn't get to the crushing department. I was doing just some helping work, around. Then another transport came and they took me up to Jáchymov and there I went through many different camps. One of the worst one was called Nikolaj, up above Jáchymov. There were German retribution prisoners[25] who were sentenced in 1945. There was always a commander and a main camp guard. Together they organized something like a little trip either at night or during the day. They went into the blocks. They chased everyone out where people had to stand sometimes in the frost and in their cells they made a huge mess. If we had food in the lockers, they stepped on it and threw it out. That was just a nightmare.

Which camps were you kept at?

If I remember well, the first camp was Nikolaj; then I went to Twelve; from there to Prokop; from there to Ležnice; from Ležnice back to Ten, and then back to Twelve. I returned there because they thought I might be a candidate to run away. Once I worked with a group that later tried to escape. I was even considered a "runaway" for a short time, because at one point I was transporting stone on small wagons from mining holes to the lift that took the stone up. One Sunday, this group didn't take me on the shift, and in the evening they tried to escape. I can tell that this was my holy luck or maybe my bad luck that I couldn't participate. For a long time they had agreed that they would try to escape and one guard even helped them. The worst was that they caught and shot them. When they brought them back to camp they just threw them on the camp like they were nothing and everyone had to walk around them. Beware to anyone who had their head down or made a cross. If you did, you were hit right away and almost knocked out. It was something horrible to see shot-dead friends. It was almost the whole of Kukal's group that tried to escape. I worked with them a couple of shifts and from this base they took me to Ruzyně[26]. I can tell you at Ruzyně I went through something similar to the "domeček." They wanted to shake or beat out from me that I knew about the escape but didn't want to tell the secret police. I knew a little bit, but I didn't have a clue that the group had agreed for a long time. Kukal wrote a book[27] then about the escape. When I met him, he signed the book and wrote me a message in it, "We escaped without you, thank God!" They actually escaped without me and saved my life this way, because if I had gone with them they probably would have shot me like the others. So then I was at Ruzyně in Prague.

What memories do you have of the prison in Ruzyně?

I was in Ruzyně for about a half year and they still tried to get out of me what I knew about the escape. Again, they tried to trap me. It was at my lowest point and I didn't think I was going to get out from the bottom. Once I even heard down in the dungeon an International song[28] being sung. There were people yelling and singing of the International song and the guards were beating them. I heard them weeping ... and it was Slánský and Co.[29] Down there in the dungeons was all of Slánský's group who were finally sentenced to death. They assigned a priest to me and I didn't know whether he was a real priest, but he continued to insist he was. They knew psychologically I was doing really bad. The priest wanted me to write a "moták" to my parents so that they would have news of me. There were a couple of months where no one knew anything about me, where I was, if I was living, or if they already shot me. The priest made me write a "moták," especially to my sister who still worked in the office of Martin Bowe. Again they wanted to prove that I was connected to this office even though Mr. Bowe wasn't there and someone else had already taken over. The priest kept saying that he had good connections through one of the guards and that they would give it to my sister. So I wrote a little message on a piece of paper that he gave me, but I did it very carefully. I told them to say hello to uncle this and that although the uncle had been dead for a while. I believed she would understand that the letter wasn't a true one. Later I found out that this priest was for sure an imposter and a confidante of the state and was assigned to me to trap me. When he gave the message to my sister out in the street, they arrested her and wanted to make her work for the state secret police. Anyway, she didn't really have time to read what was on the "moták" and they released her after about three days. She continued to work at the office for some time. So they were trying to pull such tricks on me because they were trying to get me in trouble and get me extra years in prison. When they caught someone during an attempted escape or being connected with civilians, they held a new court hearing and they gave you five more years. So I kind of saved myself this way, because it was revealed that everything that I wrote on the "moták" was false.

From Ruzyně you returned to Jáchymov?

Of course, they took me back to pit number twelve, but only for a short time. I was unlucky in that I was marked on my clothes. We had pants and on those were white stripes. Whoever had one stripe had it all right. Whoever had two, that was already a dangerous person of whom they kept a special eye on. I had an extra circle on my back as a mark that indicated I was not allowed to stop. That also meant that I was the most dangerous person for gathering people and organizing them in a group. So for the whole time I was working in the Jáchymov camps, whenever there was Christmas, May Day celebrations, or whatever different holidays, they put me in correction as soon as I got out from the pit wet and dirty. "Correction" was separate housing that was a part of the camp, a dungeon and that was where I would spend my holidays. I couldn't move around the camp because in a moment my friends came up to me and quickly we were two or three and a siren started to wail and they were indicating we were not allowed to get together. They still expected that we were getting ready to escape. I was labeled like this until the end of my stay in the working camps.

Do you remember the prison number you had in Jáchymov?

I even have them written down. My first number was 1257, but then for others I would have to look into the letters my parents were writing to me. They always had to write my prison number and "Bory" or "Karlovy Vary." So I had about three or four different numbers, but my first number was 1257.

Did you ever come across homosexuality in the camps?

No, never. Although at these camps there was something different. There were groups of people who were interested in culture, theater, and who learned languages. We mainly propagated sports. We got together with friends from Brno, Ostrava, and Slovakia. Volleyball was played there – of course, only when the work was at full stretch and the staff of the camp let us. We also played football, a match of Bohemia versus Moravia, and that was always a big event because many people came to watch. Right before I was released they even let us build a small ice rink at Camp Bytíz where we could play hockey. Bytíz was my best camp where I spent almost two years. I even remember finding a letter where I wrote to my parents to send me ice skates; and we also smuggled in pieces of wood to create barriers for the rink. That was already in the year 1955 and right after that I was released so I "unfortunately" didn't play hockey in the prison camp.

Could you summarize what comes to mind when you hear the name, Jáchymov?

A huge amount of suffering of the best people who were Czechoslovakians, or people who followed their convictions and belief took place here. They were people who knew what Communism was and fought against it. I think that Jáchymov was the suffering of a nation that can never be forgotten.

Mr. Bubník, I think this was comprehensive and thank you very much for the series of recordings we have done together.

I am really happy I can talk about it like this, because out of our group of twelve there is only Mr. Konopásek, who doesn't really remember the stories anymore, and me. Thank God "Uncle Alzheimer," who I keep chasing away, hasn't visited me yet.

Thank you very much for the interview.

External link – Various shots of the game between America and Praha LTC in progress at the Prague Winter Stadium

[1] The Czech Association of Sokol (ČOS) – a civil association which organizes voluntary sports and physical activities among the clubs of Sokol in order to promote camaraderie among its 190,000 members.

[2] Lawn Tennis Club Praha (LTC Praha) – Czech ice-hockey association (1903 - 1950).

[3] Exile – the expulsion of a man from his home country due to deportation, revoked citizenship, political, national, race or religious persecution.

[4] Sparta Club – one of the major sports club in Prague.

[5] Slavia Club – another major sports club in Prague.

[6] „Domeček" – The place in Kapucínská street in Prague-Hradčany, called "domeček" – or in Czech „little house", which is pronounced “domacheck” – was an institution of the 5th department of the Headquarters or OBZ. There, they mainly kept soldiers, who were forced to testify in certain ways via cruel inspecting methods." (source: BÍLEK, J., Nástin vývoje vojenského vězeňství v letech 1945 - 1953, s. 127.

[7] František Pergl – alias „Dry linden" or „Black penicillin," this staff captain was „only" a caretaker of the „domeček", or a janitor of the 5th department of Headquarters in Kapucínská street. Due to his service in the prewar Czechoslovakian army, Pergl was known already for his brutality. He followed every interrogator’s command to persecute prisoners and he himself made up various styles of torture.

[8] OBZ – the press agency for the Czechoslovakian army.

[9] Pankrác – prison in Prague.

[10] Dr. Milada Horáková – a Czech politician executed during the communist political processes in the fifties for putative conspiracy and high treason.

[11] Rudé právo – Translated as „Red right," this daily newspaper served the communist party until its downfall in 1989.

[12] Supreme Court – the highest Federal court which approved the last decision and against which there were no further reparations even in communist Czechoslovakia.

[13] Prison Plzeň-Bory – a prison situated in the western region of Bohemia. Under communism it was one of the strictest prisons primarily delegated for political prisoners.

[14] Mr. Trepka – the head of solitary confinement in Plzeň-Bory. He was known for his brutal practice and violence towards prisoners.

[15] Brabec – a gaurd especially known for his brutality towards the prisoners.

[16] Kremlin – Ironically, the “Kremlin” here refers to a historic fortified complex in the heart of Moscow which serves as the official residence of the President of Russia.

[17] Lenora – a small town by Prachatice, Southern Bohemia.

[18] Gulag – one of the departments of the secret police in Socialistic bloc which managed a system of concentration and working camps in SSSR. The word gulag was then used for a group of these camps and camps under this institution.

[19] Koh-i-Noor Hardmuth Inc. – a Czech producer of writing and stationary products.

[20] „Anton" – a closed police van for transport of prisoners.

[21] Podbaba – a local name for a Praha-Dejvice neighbourhood.

[22] Antonín Zápotocký – the president of Czechoslovakia at that time.

[23] „moták" – the name for secret messages usually distributed to prisoners on small pieces of paper.

[24] Jáchymov – originally a spa town close to Karlovy Vary, near the Czeschoslovak border with Germany. Working camps for prisoners were often established near uranium mines surrounding Jáchymov; political prisoners tend to call these forced labour camps "concentration" camps. Historians rather prefer “working camps,” since “concentration camp” is a term connected mainly with extermination of victims of Nazism. Concentration and forced labor camps existed in Southern Africa already in the early 20th century. Great Britain built them during the Second Boer War. In Czechoslovakia there were "retributions" prisoners but later there were also political and criminal prisoners. Prisoners were used as cheap labor.

[25] Retribution prisoners – prisoners sentenced on the basis of „retribution decrees" for cooperation and collaboration with Nazi Germany. "Political" prisoners were classified as identical to "state" prisoners, although there was a separate category for criminals.

[26] Ruzyně – the name of a Prague district and a district prison. Some well known people were kept there during the Communist regime.

[27] KUKAL, Karel: Deset křížů. (Ten crosses). Second, enlarged edition. Rychnov nad Kněžnou: Ježek, 2003. 127 p.

[28] Internationale – an international anthem of the labor movement, which is sung in many counries by communists and sometimes socialists and social democrats.

[29] Slánský Trials – Political processes launched against all sections of society, including even prominent representatives of the communist party. From 1950 onwards, the state secret police concentrated on „searching the enemy even among its own." The leading communist investigated was Rudolf Slánský, the Secretary-General of the communist party.